Discover the King of Fruits Through History, Culture, and Health

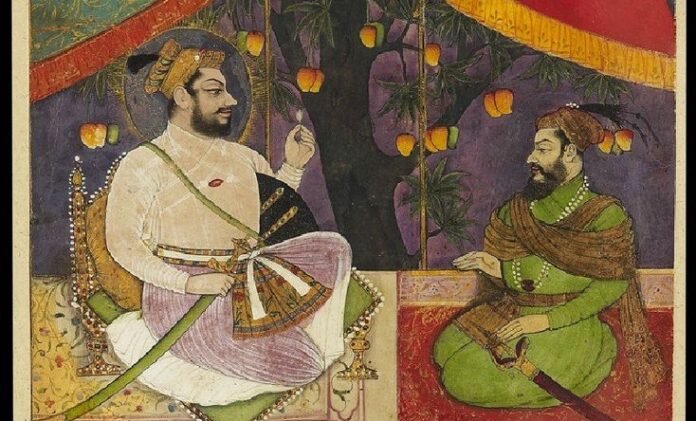

On a blistering summer day, in the court of the esteemed Akbar the Great, a dispute was brought before the emperor. Two men stood before him, both laying claim to a mango tree that grew on the border of their adjoining lands. The tree, laden with ripe, golden fruit, was the source of their contention.

The first man, whose land lay to the left, argued that the tree belonged to him since the trunk was rooted on his side of the border. The second man, on the right, contended that the tree was rightfully his, as he had nurtured it, watered it, and cared for it over the years. Akbar, renowned for his judiciousness, listened intently as each man presented his case, both fervently asserting their ownership.

After hearing their pleas, Akbar announced that his decision would be delivered the following day. The anticipation was palpable, as both men awaited the royal decree with bated breath. When the time came, Akbar declared that the tree should be chopped down, its wood and fruit divided equally between the two farmers.

The man on the left rejoiced, envisioning the profits he would gain from the wood and the bounty of the fruit. However, the man on the right fell to his knees, tears streaming down his face. He implored the emperor to spare the tree, expressing his deep affection for it and his dismay at the thought of it being destroyed.

This heartfelt plea moved Akbar profoundly. Recognizing the true love and dedication the man on the right had for the tree, he revised his decree. The emperor declared that the farmer on the right side of the land was the rightful owner of the tree. He could now continue to nurture it and enjoy its fruits in peace.

Kings Favour

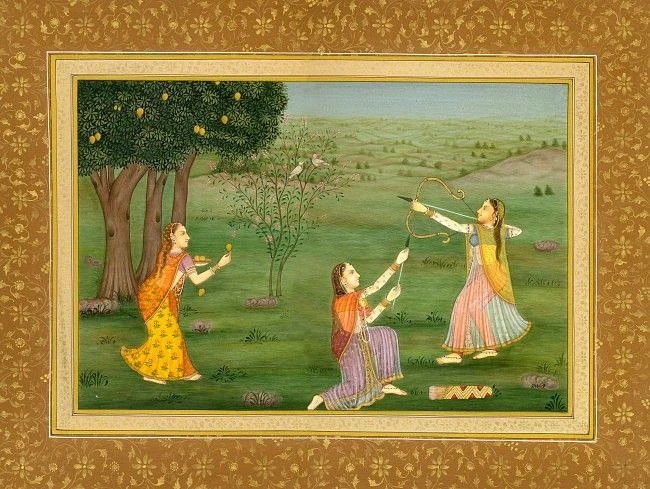

The love of mangoes is indeed special for their owners. Mango trees, with their ability to live and bear fruit for many decades, become more than mere plants; they transform into legacies. Mango orchards are often considered inheritances, passed down through generations, each tree bearing the stories and labors of those who tended them. The mango’s journey from seed to fruit, spanning years and often outliving those who first planted them, symbolizes continuity, heritage, and a deep connection to the land.

Few fruits evoke such universal delight as the mango, often celebrated as the “king of fruits.” Its rich history, cultural significance, and complex flavor profile make it a subject of reverence across the globe. From ancient cultivation practices to royal dining tables, the mango long and storied history in South Asia.

A Fruit of Antiquity

The mango traces its origins to the lush and fertile regions of South Asia, particularly in the areas we now know as India, and Bangladesh. Cultivated for over 4,000 years, the mango has left an indelible mark on the history and culture of these lands. Ancient texts and scriptures, such as the Vedas, mention the mango, underscoring its importance in early sub-continent.

The introduction of the mango to the wider world can be attributed to various historical figures and events. While the spread of mangoes across the globe involved many stages, one of the earliest significant movements came with the campaigns of Alexander the Great. Although direct evidence linking Alexander to mangoes is scant, his forays into the Indian subcontinent undoubtedly facilitated cultural and agricultural exchanges, setting the stage for the mango’s journey to Persia and beyond.

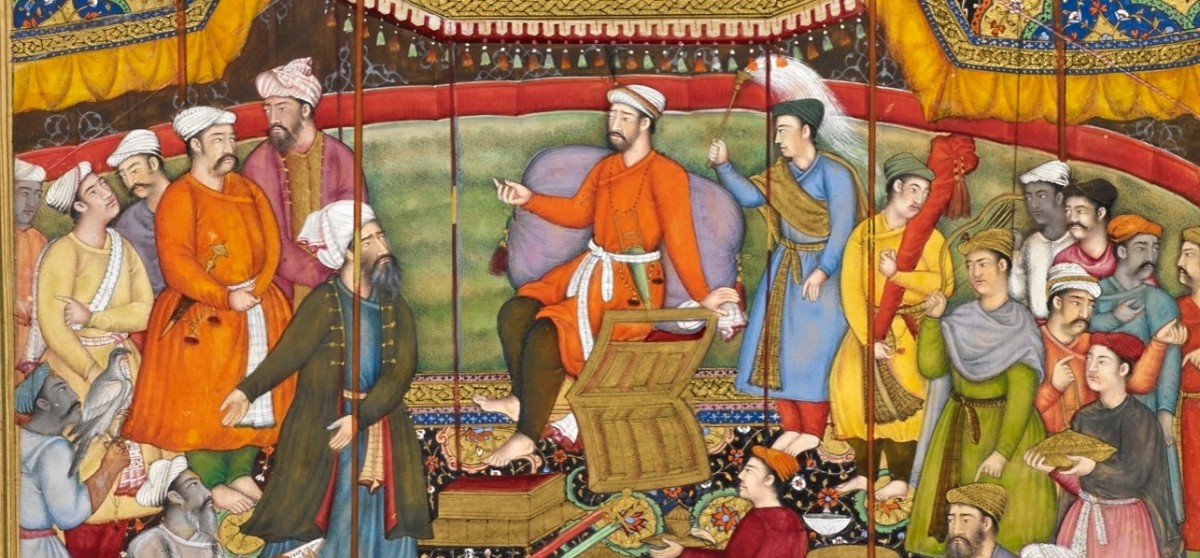

During the Mughal era, the mango’s status was elevated further. The Mughal gardens, designed with intricate waterworks and laid out in geometric patterns, often included mango orchards.

Emperor Akbar, known for his love of horticulture, established the famous “Lakhi Bagh” orchard in Darbhanga, Bihar, which reportedly housed over 100,000 mango trees. This period marked a significant advancement in mangoes’ cultivation and varietal development under imperial supervision.

Few fruits evoke such universal delight as the mango, often celebrated as the “king of fruits”.

The Science and Art of Cultivation

Native to South Asia, mangoes early cultivation practices involved selective breeding and grafting techniques to enhance the fruit’s quality and yield. The Mughal emperors, particularly Akbar, took a keen interest in these practices, establishing extensive orchards and gardens. These gardens were not only places of leisure but also centers for horticultural experimentation.

Grafting, introduced by the Portuguese in the 16th century, revolutionized mango cultivation. This technique enabled the propagation of superior varieties, ensuring a sweet taste, smooth texture, and consistent quality. The Alphonso mango, named after Portuguese general Afonso de Albuquerque, exemplifies the success of grafting with its exquisite taste and vibrant color, earning it a place at Queen Victoria’s dinner table.

Cultural Reverence

Throughout history, the mango has been more than just a fruit; it has been a symbol of fertility, prosperity, and the blessings of nature. The Ain-i-Akbari is a comprehensive document that records the administration, culture, and society of the Mughal Empire during the reign of Emperor Akbar. Compiled by his vizier, Abu’l-Fazl, it offers a detailed account of various aspects of the empire, including its agriculture and horticulture. According to scholars, while the Ain-i-Akbari does not focus exclusively on mangoes, it does provide valuable insights into the importance of this fruit during Akbar’s reign, ranging from its cultivation to economic value.

Mangoes were often exchanged as gifts among the nobility and were featured in the lavish feasts organized by the emperors. Thus to-date the tradition of sending mango crates to friends and family lives.

The fruit also found its way into poetry and literature, symbolizing love and the ephemeral nature of life. The renowned poet Amir Khusrau, who predated the Mughal era but influenced their culture, often referenced mangoes in his works.

Mangoes were utilized in a wide range of culinary creations, from desserts to savory dishes. In his travelogue, Ibn Batuta mentioned mango pickle. During Shah Jahan’s reign, Mughal chefs experimented with combining mangoes with spices, meats, and other fruits to craft elaborate and flavorful dishes.

Traditional Indian Art to Global Fame

The Ambi design, the teardrop-shaped pattern, also known as the paisley motif, is a quintessential element of Indian art. In India, it is believed to have first appeared in the region of Kashmir, where it was known as “buti” or “boteh”, symbolising fertility, and eternity. In other parts of India it was referred as “Ambi” (meaning mango).

The design’s Persian influence came through the Mughal Empire, which played a significant role in the fusion of Indian and Persian art forms. The Mughals, renowned for their appreciation of intricate and luxurious designs, embraced the Ambi motif and integrated it into their textiles, architecture, and decorative arts.

Kashmiri Shawls: A Canvas for Ambi

Kashmir, renowned for its exquisite craftsmanship and rich textile heritage, became a prominent center for the Ambi design. The intricate patterns of Ambi were meticulously hand-embroidered onto Pashmina and Shahtoosh shawls, making them highly coveted items. These shawls, often referred to as “Jamawar” shawls, featured elaborate Ambi motifs interwoven with fine silk threads, reflecting the region’s exceptional artistry.

The popularity of these shawls soared during the Mughal era, with emperors and nobility adorning themselves with these luxurious creations. The Ambi design on Kashmiri shawls became a symbol of status and elegance, revered both in India and abroad.

Image by Kashmir Connected library

Banarasi Saris: Weaving Tradition and Elegance

The Ambi design found another significant expression in the Banarasi saris of Varanasi (Banaras). Known for their opulence and grandeur, Banarasi saris are woven with fine silk and adorned with intricate motifs, including the iconic Ambi pattern. The incorporation of the Ambi design in Banarasi saris added a layer of cultural richness and artistic sophistication.

Weavers in Varanasi meticulously interwove the Ambi motifs using gold and silver threads, creating saris that were not only garments but also works of art. These saris became essential attire for weddings and special occasions, symbolizing heritage and tradition.

Block Prints: The Versatility of Ambi

Block printing, an ancient technique of printing patterns on fabric, also embraced the Ambi design. This method, particularly prevalent in Rajasthan and Gujarat, involves carving intricate designs onto wooden blocks, which are then dipped in dye and stamped onto fabric. The Ambi motif, with its fluid lines and intricate details, became a favorite among artisans.

The versatility of block printing allowed the Ambi design to be used on a variety of textiles, from cotton to silk. The patterns ranged from bold and simplistic to highly detailed and elaborate, showcasing the adaptability of the Ambi design to different artistic styles and preferences.

Modern Adaptations

The global appeal of the Ambi design surged during the British colonial period. British officers and traders who visited India were enamoured with the intricate patterns and luxurious textiles, leading to the export of Kashmiri shawls and other Ambi-adorned fabrics to Europe. The motif gained immense popularity in Europe, particularly in the town of Paisley in Scotland, from which it derives its Western name.

In contemporary fashion, the Ambi design continues to inspire designers and artists worldwide. It is seen on a diverse range of products, from haute couture to everyday apparel, home decor, and accessories. The timeless elegance of the Ambi motif makes it a perennial favorite, transcending geographical boundaries.

The Stories Behind Mango Names

There are fascinating stories behind the names of mangoes, often reflecting historical events, personal legacies, and regional pride.

Chaunsa

The Chaunsa mango, named by Sher Shah Suri to commemorate his 1539 victory over Humayun at the Battle of Chausa, is celebrated for its sweet, juicy flesh and distinct flavor. This naming act immortalized both his triumph and the mango, making it a beloved variety in Pakistan.

Anwar Ratol

Initially planted in Ratol, Uttar Pradesh India, a mango grafter carried his expertise to Pakistan, naming the fruit “Anwar-ul-Haq” after his father. Over time, it became known as “Anwar Ratol,” blending his father’s name with his native village.

Sindhri

Originating in Pakistan’s Sindh province during the early 1930s British colonial period, the Sindhri mango was first cultivated in Mirpurkhas’ fertile lands. Celebrated for its large size, vibrant yellow color, and sweet flesh, this mango reflects Sindh’s agricultural pride and enjoys international acclaim today.

Langra

The Langra mango, originating 250-300 years ago in Banaras, India, was named after a lame man, “Langra,” who planted a seed in his backyard. This tree’s mangoes, known for their fleshiness, gained local popularity. Today, Langra mangoes are celebrated for their unique flavor and texture, symbolizing humble beginnings and ingenuity.

Dasehri

The Dasehri mango originated near Dasheri village, close to Lucknow, India, first grafted by Abdul Hameed Khan Kandhari. Gaining popularity, it reached the Nawabs’ opulent gardens, who cherished its smooth, non-fibrous flesh and sweet flavor. The Nawabs’ appreciation boosted its widespread cultivation and culinary incorporation.

Best Way to Eat Mangoes

In Ayurveda, mangoes are celebrated for their health benefits, delicious taste, and ability to balance the doshas (body constitutions) when consumed mindfully. The fruit’s rich nutritional profile supports overall well-being, from aiding digestion to boosting immunity. However, it is crucial to consider Ayurvedic principles regarding food combinations and dosha-specific guidelines to harness the full benefits of this “king of fruits.” Enjoy mangoes in their season, pair them with complementary foods and spices, and savor their natural goodness in harmony with Ayurvedic wisdom.

Prime Combinations

Mango tends to create heat in the body. If large quantities are consumed, it can cause pimples and diarrhea. To cool the body, it is highly recommended to drink cold milk after consuming this fruit. Some cooling spices like cardamom and saffron can be added to the milk. This method nourishes the body and gives a glow to the skin.

Mango and honey: Ayurveda specifically mentions adding honey to mango pulp to cure respiratory conditions.

Mango Chutney: Often made with unripe mangoes, spices, and herbs, this chutney balances the sourness of the unripe fruit with digestive spices like cumin, fennel, and ginger.

Beat the Heat: Take unripe mango and boil it for 10 minutes in water. Once done, let the concoction cool down. Blend it with sugar to make a smoothie and enjoy it on a hot summer afternoon. This drink is recommended for dehydration and sunstroke.

Food Combinations to Avoid

Ayurveda strongly advises against certain food combinations with mango to prevent digestive disturbances and toxin formation:

Mango and fermented dairy: Combining mango with yogurt or cheese can cause digestive issues and toxin buildup.

Mango and Fish: This combination is highly incompatible and can lead to the formation of toxins in the body.

Mango and Sour Fruits: Combining mango with other sour fruits like citrus can cause fermentation and digestive issues.