Air Vice Marshal (R) Aftab Hussain brings to the conversation a rare combination of military discipline, public-sector leadership and long-term commitment to humanitarian service. A decorated officer of the Pakistan Air Force with 35 years of distinguished service, he has been awarded Hilal-e-Imtiaz, Sitara-e-Imtiaz, and Tamgha-e-Imtiaz, and has held senior roles including Director General Civil Defence at the Ministry of Interior. In recent years, he has devoted his experience and authority to the social sector as Director of the Sundas Foundation, one of Pakistan’s foremost institutions working for the treatment and prevention of thalassemia and other blood disorders. His transition from national security to public health reflects a belief that some of the country’s most urgent battles are now being fought

far from the battlefield, in hospitals and policy rooms.

Pakistan continues to grapple with diseases that much of the world has already consigned to history. Thalassemia, an inherited blood disorder that can be prevented through policy, awareness, and early testing remains a silent crisis. While countries such as Cyprus, Iran, Turkey, and even the Maldives have successfully controlled or eradicated it, Pakistan today has nearly 100,000 patients suffering from major thalassemia and millions of unaware carriers.

To understand why the disease persists, and what can realistically be done to stop it, Margalla Tribune spoke to Air Vice Marshal (R) Aftab Hussain, Director of the Sundas Foundation, one of Pakistan’s leading institutions working for the treatment and eradication of thalassemia.

MT: How did you become involved in thalassemia work?

AVM Aftab: Initially, I knew very little about thalassemia, only that children suffering from it require regular blood transfusions. While serving on the Board of Governors of a university project in Jhang, people repeatedly approached me and told me there was no thalassemia center in the district. Families had to travel to Faisalabad or Lahore for treatment.

When I returned, I searched online for organizations working in this field and came across the Sundas Foundation. I visited their Lahore center in Shahdara in 2017. When I met the children and their families, I was deeply shaken. One moment changed everything for me. I asked a young child what he wanted to become when he grew up. His mother quietly said, “Sir, I don’t know if he will grow up or not.”

That was the moment I decided to volunteer my services. For nearly a decade now, I have been associated with Sundas Foundation. Today, we run 12 to 13 centers across Pakistan, and I oversee the Islamabad facility in F-9 Park as well as serve as Director of the Foundation.

MT: What exactly is thalassemia?

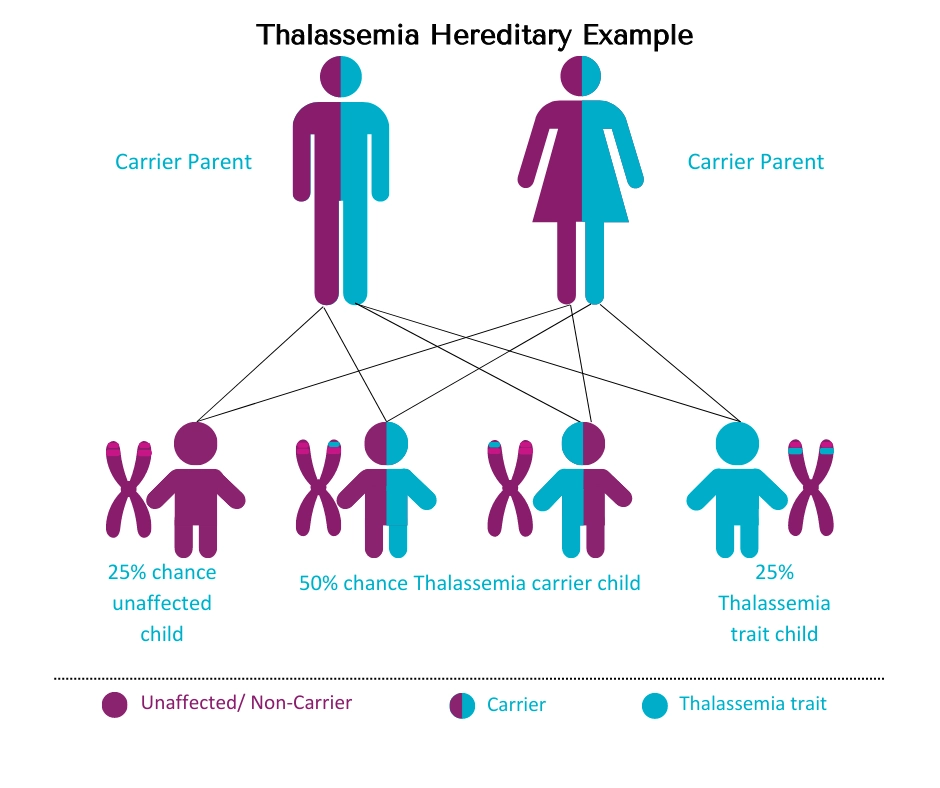

AVM Aftab: Thalassemia is a terminal and potentially fatal genetic disease. It is inherited from parents before birth. The parents themselves are usually carriers and live normal lives, often unaware of their status.

The problem arises when two carriers marry. In such cases, there is a 25 percent chance that the child will be born with major thalassemia, a 50 percent chance the child will be a carrier, and a 25 percent chance the child will be completely normal.

It is inherited from parents before birth. The parents themselves are usually carriers and live normal lives, often unaware

There are no shortcuts to success. In developed countries, becoming a professional takes years of hard work. Do not expect the government to fix your life, that is a losing mindset. Hard work, discipline and integrity remain the only real path forward.

MT: Is thalassemia more common in first-cousin marriages?

AVM Aftab: It is significantly more pronounced in cousin marriages, simply because carriers are more likely to marry within the same family. In Pakistan, we currently have around 100,000 patients with major thalassemia and an estimated 2 to 3 crore carriers. Tragically, most carriers do not know they are carriers because they have never been tested.

I have personally seen families in areas like Mardan and Swabi where all children of the family were affected, even though statistically the probability is 25 percent.

Thelisima is significantly more pronounced in cousin marriages

MT: How is thalassemia diagnosed? Can it be detected in routine blood tests?

AVM Aftab: A routine blood test may raise suspicion, but a definitive diagnosis requires a hemoglobin electrophoresis test, conducted using a specialized analyzer. This test determines whether a person has thalassemia minor or is a carrier.

A routine blood test may raise suspicion, but a definitive diagnosis requires a hemoglobin electrophoresis test.

MT: What happens physiologically to a child with major thalassemia?

AVM Aftab: The disease affects hemoglobin as the protein responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body. In major thalassemia, this hemoglobin is defective. A healthy male should have an Hb level of around 13.5 and a female around 12.5. Thalassemia patients often have Hb levels as low as 5 or 6 from early childhood.

As a result, these children suffer from severe anemia from birth. To survive, they need lifelong blood transfusions, usually four to five times a month. However, frequent transfusions cause iron to accumulate in the body, which damages organs. To counter this, patients must take iron chelation therapy, either orally or through injections administered over several hours. This treatment is physically and emotionally exhausting.

MT: Many countries have successfully eradicated thalassemia. What did they do differently?

AVM Aftab: The best example is Cyprus. In 1976, it had the highest thalassemia burden in the world. The government made thalassemia testing mandatory before marriage. Similar policies were later adopted by Italy, Turkey, Iran, Qatar, and the Maldives.

However, legislation alone is not enough. These countries first invested heavily in awareness and education. People were taught what thalassemia is, how it affects families, and how it can be prevented. As awareness increased, people voluntarily started getting tested.

In Sri Lanka, thalassemia testing is compulsory at the school level, and the reports are sent directly to the Ministry of Health.

MT: What happens if thalassemia is not detected early?

AVM Aftab: Without treatment, a child with major thalassemia usually dies within the first three years. With treatment, the average life expectancy in Pakistan is around 15 to 20 years. However, with high-quality care including screened blood, timely medication, and regular monitoring of the heart and liver, patients can live into their late twenties or thirties. At Sundas Foundation, we have patients who are over 35 years old.

MT: Your centers also treat other blood disorders. Could you tell us about them?

AVM Aftab: We also treat hemophilia, a disorder caused by a deficiency of clotting factors VIII, IX, or X. In such patients, bleeding does not stop easily, even from minor injuries. Treatment involves transfusion of fresh frozen plasma or factor injections, which can cost between Rs. 40,000 and Rs. 50,000 per dose, far beyond the reach of most families.

MT: Blood donation is central to your work. How serious is Pakistan’s blood shortage?

AVM Aftab: It is extremely serious. Internationally, 40 to 90 percent of blood donations are voluntary. In Pakistan, only about 12 to 13 percent are voluntary. Around 70 percent are replacement donations from relatives, and nearly 20 percent come from professional donors, many of whom are addicted and carry unsafe blood.

Screening is another major issue. Outside major cities, only 30 to 40 percent of blood is properly screened. This leads to transmission of diseases such as AIDS, Hepatitis B and C, syphilis, and malaria, particularly dangerous for thalassemia patients. At Sundas Foundation, every unit of blood is thoroughly screened before transfusion.

MT: What are the main reasons Pakistan has failed to control thalassemia?

AVM Aftab: The biggest reason is the lack of government priority. To date, there is no national policy on thalassemia. There is no comprehensive patient registry. We do not even know the true number of patients.

Testing should be linked with NADRA, driving licenses, and national awareness campaigns. Legislation must be followed by strict implementation.

MT: What’s the biggest challenge that Sundas Foundation encounters?

AVM Aftab: The biggest challenge is arranging blood. We have around 700 patients and need 400 to 500 bags of blood every month. Financial constraints have increased due to inflation. Donations have declined as people struggle with basic expenses. NGOs like ours need structured support from both provincial and federal governments.

MT: What is your message to policymakers and the public?

AVM Aftab: Thalassemia is preventable. No child should be born to suffer lifelong pain when simple testing can stop it. Awareness, testing before marriage, and responsible policy implementation can eradicate this disease. If other countries can do it, Pakistan can too, if we choose to.