Part 1

…Given our unbroken streak of no revolutions since Harappa, four reasons suggest that the future holds little promise for upheaval or radical transformation: our reflexive return to the man-on-thehorseback governance model, our penchant for Jurassic Park-style political resurrections, our misplaced faith in the so-called revolutionary potential of digital social media, and the fact that we lack the inspiring leadership that could steer us toward true systemic, costly, and difficult transformation (vertical change).

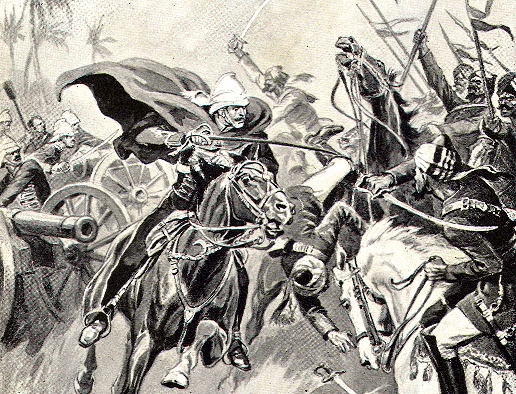

First, during extreme crises, instead of pursuing the alternative of revolutionary change, we are

more likely to revert to our core governance model—the rule of the man-on-the-horseback. Why?

Under pressure, we tend to choose the risk-averse route. Rather than experimenting with new systems or ideologies, we prefer to rely on and revert to what has proven “effective” in the past to safeguard against the looming threat of anarchy.

A steady sequence of military-founded dynasties dominated our history, where the founder-general

co-opted the “native” elite to provide bureaucratic support and maintain control. Their effectiveness in governance conferred legitimacy; order was preferred to anarchy. However, most of these dynasties were often short-lived. The polygamous nature of the royal houses led to an overabundance of heirs, creating sibling rivalry and infighting and ultimately undermining the dynasty’s stability. As one discordant dynasty faltered, a new founder-general emerged, bringing fresh energy and forces to claim the throne and establish yet another reign, sometimes brief, sometimes prolonged.

Even the Raj followed this model, where foreign men-on-the-horseback co-opted the “native” elite. The only notable change was that, unlike previous dynasties, the Raj’s founder-generals did not permit their children to inherit power. Instead, newly appointed colonial officers from the British Isles were dispatched to govern our land. After the Raj’s departure, the same model persisted. Our post-colonial founder-generals continued to co-opt domestic political, bureaucratic, literary, and economic elites as junior partners.

Second, even if, by some improbable stroke of luck, we contrive to sidestep the ever-recurring loop of reverting to our man-on-the-horseback governance model, we risk rushing headlong into a Jurassic Park fantasy, fixated on resurrecting a mythologized past rather than creating something genuinely new, progressive, and benevolent. If a truly revolutionary upheaval indeed erupts, we may be marching backward through time instead of progressing toward modernization and change.

We often neglect that no revolution arises from the Jurassic Park reconstruction projects. Tired and declining civilizations look backward, not forward; they envision their utopias as echoes of some lost golden age and rush to return to it through the dust of myth and memory. They romanticize the past, seek salvation in antique narratives, and draw plans from knowledge long since fossilized. In contrast, vibrant and ascending civilizations cast their hopes ahead. Their utopias lie in uncharted futures, not in sepia-toned histories. They plan boldly, adapt restlessly, and reach for solutions that did not exist before—fueled by innovation, not nostalgia.

“…we look to the past as though it contains a magic formula for how we should live. In truth, the past was neither better nor worse than what we have now; it was just more varied. As far back as we can see, humans have landed on rainbows of different ways of organizing themselves, always negotiating the rules…Nothing has ever been static. Over millennia, we’ve been pushed gradually into believing that there are just a few ways in which we can live. Our societies have been homogenized through colonization…Our institutions of government have ossified to the point where they feel immovable…We resign ourselves to the systems we have, even when we know they’re not working. It’s no surprise, given this inertia, that we feel the social patterns we follow must be natural or (ordained)…”. (Angela Saini: The Patriarchs: The Origins of Inequality).

If, in the future, urban upheaval by unmoored masses surpasses the controlling capacity of our

dysfunctional ancien régime, the real fear is that we may divert and deploy that urban pressure to initiate our own Jurassic Park reconstruction project. Instead of channeling urban discontent into meaningful reform, we may veer toward regressive, extremist solutions, reviving archaic ideologies rather than forging radical, forward-looking change.

Third, many passionately argue that digital social media is a revolutionary force destined to end the long winter of our history and usher in our long-awaited “spring” of radical change at any moment. However, this faith in the transformative potential of these technologies is profoundly misplaced. The for-profit global elite so thoroughly monopolizes the immense power of digital platforms that those who believe these tools will ignite real change are living in a fool’s paradise. If anything, digital technology is steering us backward rather than forward. Far from being instruments of liberation, these new technologies have become the most sophisticated tools for capturing, consolidating, and concentrating power in the hands of the political elite.

A question then looms: Are we genuinely advancing, or are we merely heading back to the future?

An era of neo-feudalism, repackaged in pixels and push notifications? Yes, millions are now concentrated in sprawling urban centers. These once-isolated villagers-turned-urbanites hold countless digital devices in their hands. And yet, despite all these so-called empowering technologies at their fingertips, they are not rising in protest. Why? Because these new digital tools, rather than empowering them, have become instruments of distraction, diversion, and pacification.

The very platforms that should fuel dissent instead manufacture consent, keeping the masses entertained, engaged, and ensnared. The lumpen masses are often more eager to swarm free streaming platforms than to storm the barricades. Thanks to these “revolutionary” new digital technologies, their cognitive energies are dissipated into memes, cat videos, hashtags, and viral dance challenges. What an irony: millions of farmers migrated from the solitude of their farms to the crowded cities, and what did they find—the solitude of screens?

“Unfortunately, four decades of digital technology deployment have undermined the sharing mechanisms that were developed earlier in the twentieth century. And with the arrival of artificial intelligence, our future begins to look disconcertingly like our agricultural past.” (Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson: Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology And Prosperity).

A question then looms: Are we genuinely advancing, or are we merely heading back to the future— an era of neo-feudalism, repackaged in pixels and push notifications? Yes, millions are now concentrated in sprawling urban centers. These once-isolated villagers-turned-urbanites hold countless digital devices in their hands. And yet, despite all these so-called empowering technologies at their fingertips, they are not rising in protest. Why? Because these new digital tools, rather than empowering them, have become instruments of distraction, diversion, and pacification. The very platforms that should fuel dissent instead manufacture consent, keeping the masses entertained, engaged, and ensnared. The lumpen masses are often more eager to swarm free streaming platforms than to storm the barricades. Thanks to these “revolutionary” new digital technologies, their cognitive energies are dissipated into memes, cat videos, hashtags, and viral dance challenges. What an irony: millions of farmers migrated from the solitude of their farms to the crowded cities, and what did they find—the solitude of screens?

The writer is a lawyer & can be contacted at asim_ali@ksg03.harvard.edu