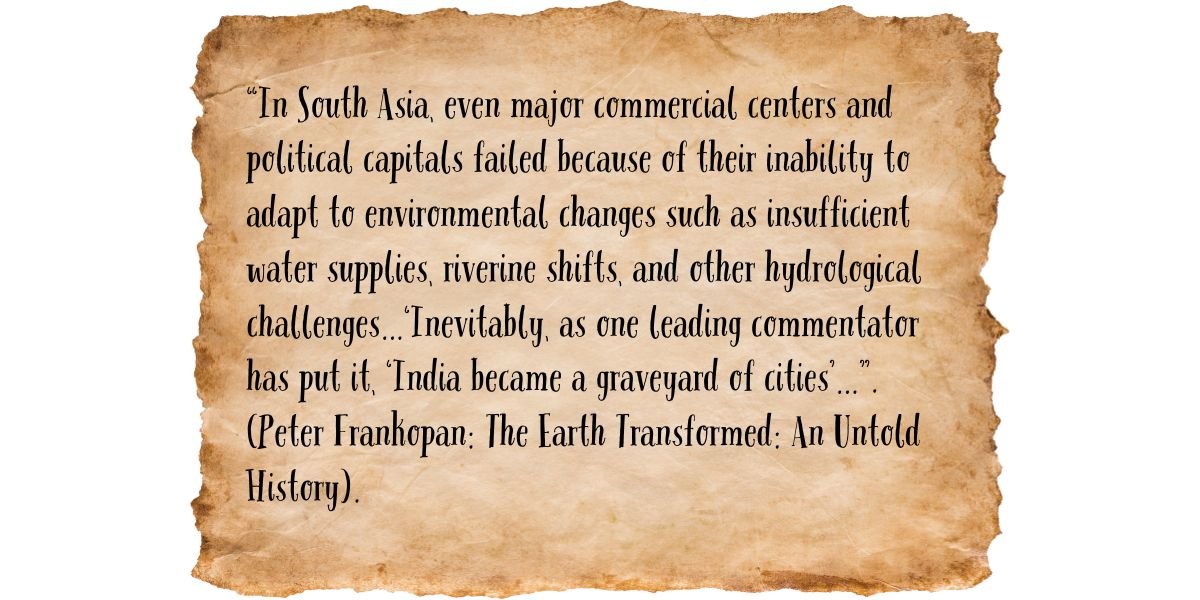

Going all the way back to the Harappan civilization (circa 2500 BCE), the Indian subcontinent has never experienced a true revolution. This means there has never been a mass uprising that led to a fundamental vertical change in societal structure and power dynamics. The people never rose, seized their fate, and forged a new order. Rebellions? Many. Monarchs toppled? Numerous. Invasions? Multiple. The imperial regime changes that we often remember were horizontal power swaps among competing elites, not the seismic and vertical upheavals from below that redefine a society.

The distinction between revolts and revolutions may not carry the same weight it once did for the king who lost his head over confusing the two, but it remains crucial when evaluating the true motives, manifestos, and machinations of those who seek our consent, contributions, and cash for their grand plans, policies, and proposals. A practical method for assessing conflicting political agendas is to ask: Does this proposal aim for a horizontal change (rearranging power among the existing elites), or does it call for a vertical shift (radically overhauling the system and devolving power)? The former may sometimes represent rebellions or revolts, while the latter often signifies a genuine, transformative revolution.

The distinction between revolts and revolutions may not carry the same weight it once did for the king who lost his head over confusing the two, but it remains crucial when evaluating the true motives, manifestos, and machinations of those who seek our consent, contributions, and cash for their grand plans, policies, and proposals. A practical method for assessing conflicting political agendas is to ask: Does this proposal aim for a horizontal change (rearranging power among the existing elites), or does it call for a vertical shift (radically overhauling the system and devolving power)? The former may sometimes represent rebellions or revolts, while the latter often signifies a genuine, transformative revolution.

Revolts are typical examples of horizontal changes. Elite factions squabble over who gets to steer the ship without altering its course. During revolts, new elite cliques aim for a larger share of power. Their rallying cry does not advocate devolving power to the hoi polloi or achieving social justice for the masses, but rather for a forced or fair power transfer to a different elite faction! The disruptive elite who revolt merely seek some seats at the table, not to overturn the dining room; they want to participate in the system instead of dismantling it. Revolts resemble a game of musical chairs, an elite reshuffle. They involve a change of guards who claim that they are necessary for the preservation, survival, and restoration of the existing system; hence, during revolts, we typically hear about the infusion of “fresh” blood to enhance the decaying system’s efficiency.

On the other hand, revolutions tend to demand and deliver vertical changes. The objective of revolutionary people is not inclusion but the complete demolition of the ancien régime and its replacement with a more equitable and, if possible, more equal form of polity. The revolutionaries do not want to enter the elite club but padlock it and create alternative, new governance models: they demand and deliver a de novo beginning. Revolution is about the whole company going bankrupt; a new system, outlook, vision, and management replace it. It is not about resuscitating the old corporation with fresh blood but about discarding the system and adopting radical new structures.

One distinguishing feature of a revolution is the emergence of brand-new faces, most of whom have never been in the capital, let alone in the power corridors: Who is she? Though revolutions flare with hope and fracture the old triad, they ultimately crown new potentates, princes, and prelates—as the iron law of oligarchy grimly reminds; yet in their blaze, they give groups a second chance to imagine power differently, however briefly.

Many factors have influenced the absence of a revolutionary groundswell in the history of the Indian subcontinent since Harappa. Three stand out: the lack of urban density, the superficial “transfer of power” at the time of decolonization, and the deeply entrenched belief in predestination. The lack of urban density hindered mass mobilization. While not an absolute prerequisite, urban crowding has historically provided a breeding ground for revolutionary energy—a necessary, though not sufficient, catalyst for upheaval. Many countries only experienced seismic social change after millions migrated to densely populated urban centers.

When peasants migrate en masse to urban areas, they are thrust into unfamiliar social, economic, and political landscapes that can ignite collective action and, in some cases, even revolutionary movements. Discontent with the dire conditions under which millions are forced to live begins to build. In the grimy slums and squatter settlements, the displaced peasantry feels abandoned. They perceive that the old-world certainties and securities are crumbling. Cramped into these tight spaces, they become receptive to the whispers of new futures, sometimes idealized or utopian.

In these crowded environments, dynamic yet opportunistic commercial classes emerge—hungry for profit and restless for growth. Driven by their economic ambitions, these rising commercial forces often advocate for transformative reforms to advance their upward mobility. The revolutionary spirit typically burns brightest among the urban elite and slum dwellers. When the new urban elite and the slum dwellers unite to demand vertical change, the old regimes tremble— and sometimes crumble.

Such revolutionary moments often mark the beginning of genuine transformation, triggering modernization’s uneven and halting march. In this changing landscape, many nations are granted a second chance—an opportunity to break free from the past and reshape their future. Nearly every country that later rose to great-power status first pressed its social reset button, dismantled its ancien régime, and began anew. Britain (1688), the United States (1776), France (1789), Japan (1868), Russia (1917), Turkey (1923), and China (1949) all embarked on their transformative journeys only after such foundational ruptures—fresh starts that redefined their destinies.

That is, however, not the story of the subcontinent. For centuries, our pliant peasants remained tied to their villages, tethered to their land, with their fates sealed in soil. They were spread across expansive rural landscapes, making a collective uprising against the entrenched elite not only unlikely but logistically unfeasible. The sheer distances between villages rendered mass coordination a Herculean task—the nearest potential co-conspirator, the would-be “comrade,” was often miles away. How could millions of peasants, spread across thousands of remote villages, ever come together, act as an urban underclass, and spark a revolution demanding vertical change? Beyond the barriers mentioned above was an additional challenge: the temperament of farmers. Bound by the slow rhythms of subsistence farming, they often lacked the ideological inclination to join revolutionary movements. While peasants occasionally rebelled, their efforts seldom led to transformative change.

Migration to cities was rare; few towns existed to migrate to. Nehru referred to India as half a million villages. Thus, India persisted as a vast expanse of villages, each a world unto itself. In the few urban centers that did exist, there was no true underclass to experience the power of numbers, no furnace of discontent to forge upheaval. There was no revolutionary spark, no reset button demand—only the farmers’ slumbering lives and the ancien régime’s lumbering endurance continuing the imperial drama of horizontal change—the traditional game of musical chairs among the elite sections. The village never came to the city, the old order never fell, and the new start was never made.

When the time for decolonization came, it presented an opportunity for implementing change. However, that never transpired. Decolonization was merely a superficial “transfer of power,” not a fundamental rupture. The post-colonial elites smoothly stepped into the roles of the departing British rulers. Thus, the chance for effectuating a radical and beneficial transformation after decolonization was squandered: no reset was initiated, and no vertical change occurred. 1947 marked only a horizontal shift in power.

Not only did our newly empowered elite sidestep the possibility of fundamental change; on the contrary, they took active measures to entrench the status quo in the post-colonial era. The land allotment policy in Pakistan after 1947 serves as a telling example. Millions of migrants from India to Pakistan, having left behind their hearths and homesteads, were informed upon arrival that they would receive land only in proportion to what they had owned in the old country. The elite’s rationale was simple: the turmoil of 1947 was to be managed, not leveraged for revolutionary transformation. Land redistribution and structural reform were off the table. The result? The old hierarchies persist to this day. Despite the appearance of change, the ruling elites in successor states continue to dominate, much as they had for centuries before.

Some may argue that this is old history—things have changed. Millions of farmers have left their villages in recent decades and flocked to sprawling urban centers. Now, one-third of the population in the subcontinent lives in urban towns and experiences the power of numbers. This is a significant figure in terms of subcontinental history. The oftcited necessary condition for the revolutionary furnace to ignite—masses crowded into urban slums, squatter settlements, and shantytowns—has now been fulfilled. And yet, there is hardly a clamor for vertical change. The elite remain safely seated in the saddle, just as they have for centuries before these new urban centers emerged.

Multiple factors could explain this mass inertia, but the most critical is a worldview steeped in predestination—a belief that has dulled the appetite for radical change. When destiny is preordained, how can one even imagine curating new futures? If all is fated, why struggle to press the reset button? Drilled into the masses by prelates for centuries, this doctrine assured them that the “system” was cosmically ordained, immutable as the stars. This fatalistic outlook, reinforced over generations and fused with the isolation of village life, ensured that mass uprisings against the elite remained as rare as unicorns—unchanging since the days of Harappa.

“Rather than taking the rise of science to be the literal cause of the growth of political liberty, both science and political liberty would be better regarded as the joint outcome of an antecedent cause. This antecedent cause is the freeing of the human mind from the trammels of doctrinal orthodoxy aspirations to liberty of religious conscience in the sixteenth century rapidly evolved into demands for liberty of thought and enquiry in all fields, including science; and once people had asserted the right to think for themselves without conforming to a dogma on pain of death, they were able to ask questions both about nature and about sociopolitical arrangements. On this view, science and democracy grew together from a fundamental impulse towards liberty and are its joint fruits.” (Anthony Clifford Grayling: The Challenge of Things: Thinking Through Troubled Times).

Does all this historical baggage—lack of urban density, problems of peasant coordination and temperament, squandered opportunities for transformation during decolonization, and an ingrained outlook of fatalism that impedes radical change—indicate that Pakistan will never undergo a radical shift in power dynamics? Or are we on the cusp of seismic sea change—about to press the reset button, dismantle our ancien régime, and seize a second chance to reshape our future?

Lao Tzu once said, “Those who have knowledge don’t predict. Those who predict don’t have knowledge.” Sometimes, it is wise to resist prophecy; history is a blend of change and chaos, chance and contingency, choice and consequence, with entropy lurking in the background. Yet, as Winston Churchill reminded us, “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” History may not always repeat, but it often rhymes.

Given our unbroken streak of no revolutions since Harappa, four reasons suggest that the future holds little promise for upheaval or radical transformation: our reflexive return to the man on the horseback governance model, our penchant for Jurassic Park-style political resurrections, our misplaced faith in the so-called revolutionary potential of digital social media, and the fact that we lack the inspiring leadership that could steer us toward true systemic, costly, and difficult transformation (vertical change).

The writer is a lawyer & can be contacted at asim_ali@ksg03.harvard.edu