Weddings, Gossip, & Honour

In Punjab, marriage is not simply a contract between two people; it is a carefully woven social drama where kinship, honor, gossip, and tradition intertwine. Villagers often warn: “Do not marry a daughter into your own village; the gossip will travel faster than she can.” In this saying lies the truth of Punjabi society—relationships are never private matters. They are public performances, staged before neighbors, kin, and the wider biradari (lineage group), where the smallest whispers can shape reputations for generations.

Biradari: The Social Spine of Marriage

The biradari system in Punjab is the backbone of social life. It is a patrilineal kinship network, where honor, izzat, is measured not only by wealth but by reputation, alliances, and adherence to cultural norms. Within this structure, marriage is less about two individuals and more about the placement of entire families within this social web.

Parents begin to think seriously about marriage when their son reaches seventeen or eighteen. For daughters, the socially sanctioned age has historically been younger, between fifteen and twenty. Delay carries stigma. A son or daughter left unmarried beyond the “right age” is seen as a reflection of parental negligence or incapacity. Families fear whispers that they are incapable of performing their duties, whispers that erode their izzat.

Thus, the urgency is real. Whether wealthy landlords or struggling farmers, parents set themselves to the task of arranging marriages, even if it means borrowing money, pawning land, or finding creative alternatives to ensure that their children wed “on time.”

The Cost of Marriage: Borrowing, Bartering, and Vatta Sata

Marriages in Punjab are rarely small affairs. Even the poorest families feel pressure to host ceremonies befitting their status. A family that cannot conduct rituals properly risks humiliation. To avoid shame, many borrow heavily or rely on social arrangements like Vatta Sata.

Vatta Sata literally means “give and take.” It is a system of exchange marriages: a family agrees to give a daughter or niece in return for a bride for their son. While this solves the immediate problem of finding matches, villagers whisper warnings: “There will be trouble.” If one couple quarrels, the other feels compelled to follow suit, creating a chain reaction of discord. Yet necessity often overrides fear, especially among the poor.

Other forms of compromise exist. Sometimes the boy’s family offers a sum of money to the girl’s family, discreetly acknowledged but never openly celebrated. The money may be used for the bride’s dowry and the wedding reception, but it is considered a lesser form of marriage, one that families are reluctant to admit.

Among wealthier households, where resources are less constrained, marriage planning begins only once the family feels financially secure enough to shoulder the burden of ceremonies. Here, Vartan Bhanji, the exchange of gifts, takes center stage, signaling not only union but prestige. Families with means spare no effort in ensuring that rituals reflect their social standing.

Rituals of Prestige: Vartan Bhanji

Perhaps the most culturally significant part of Punjabi marriage is Vartan Bhanji. This practice of reciprocal gift exchange is more than generosity; it is a reaffirmation of kinship, a public display of relationships, and a performance of status.

During weddings, kin and non-kin alike exchange gifts ranging from clothes to sweets, reinforcing bonds that stretch beyond the immediate families. Parents see these rituals as investments in their child’s future izzat. By gifting generously, they not only please in-laws but also strengthen their own position within the biradari.

Even the humblest families strain themselves to perform Vartan Bhanji, knowing that weddings are moments when reputation is forged or fractured. For parents, it is less about pleasing the child and more about ensuring that the child carries honor into the new household, where the weight of judgment will be equally heavy.

The Shadow of Child Marriage

Child marriage, though increasingly rare today, has historically been part of Punjab’s marriage landscape. In such unions, ceremonies are performed, dowries exchanged, and the young bride may even visit her husband’s household. Yet consummation is delayed until after puberty, usually when the girl is between fifteen and eighteen.

In these years, a curious pattern unfolds: the child-husband visits his young wife’s family, plays with local boys, and gradually forms a bond of friendship with her. In some cases, the girl goes to live with her in-laws, where her mother-in-law trains her in household duties. What might appear oppressive from a modern lens was understood locally as preparation for an early apprenticeship in running a home.

While such practices are now widely criticized and legally discouraged, they reveal how marriage in Punjab historically blurred the lines between childhood and adulthood, weaving social duty into every stage of life.

Marriage as Alliance, Not Romance

In the Punjabi imagination, marriage is a strategic alliance. Romantic love, as celebrated in modern media, finds little space in traditional arrangements. Parents investigate the prospective family’s reputation, financial stability, relationships within their biradari, and even the standing of the maternal family (nanke). A spouse is seen less as an individual and more as a representative of a family’s collective character.

Even physical traits, skin shade, comeliness, and relative age are weighed carefully. Ideally, the couple should be close in age, but poverty often compels compromises. In poorer households, a boy may be given a much older bride, simply because opportunities are scarce and daughters are too precious to leave unmarried. Marriage, then, is about continuity, not novelty. It is about knitting two lineages together, strengthening old ties, or forging new ones to be nurtured over generations.

Endogamy and the Comfort of Kin

Endogamy, the practice of marrying within one’s group, remains a cornerstone of Punjabi marriages. Zamindar families prefer to arrange matches within their own class, while cousin marriages, both cross-cousin and parallel-cousin, are common. Families believe marrying within the kin keeps property intact and strengthens loyalty within the lineage.

“To marry one’s daughter to a stranger,” villagers say, “is to expose the family’s shortcomings.” Yet when no suitable kin is available, families extend ties outward. If the new alliance proves beneficial, further intermarriages often follow, binding the two families across multiple generations.

Ceremonies of Belonging: The Bride’s Journey

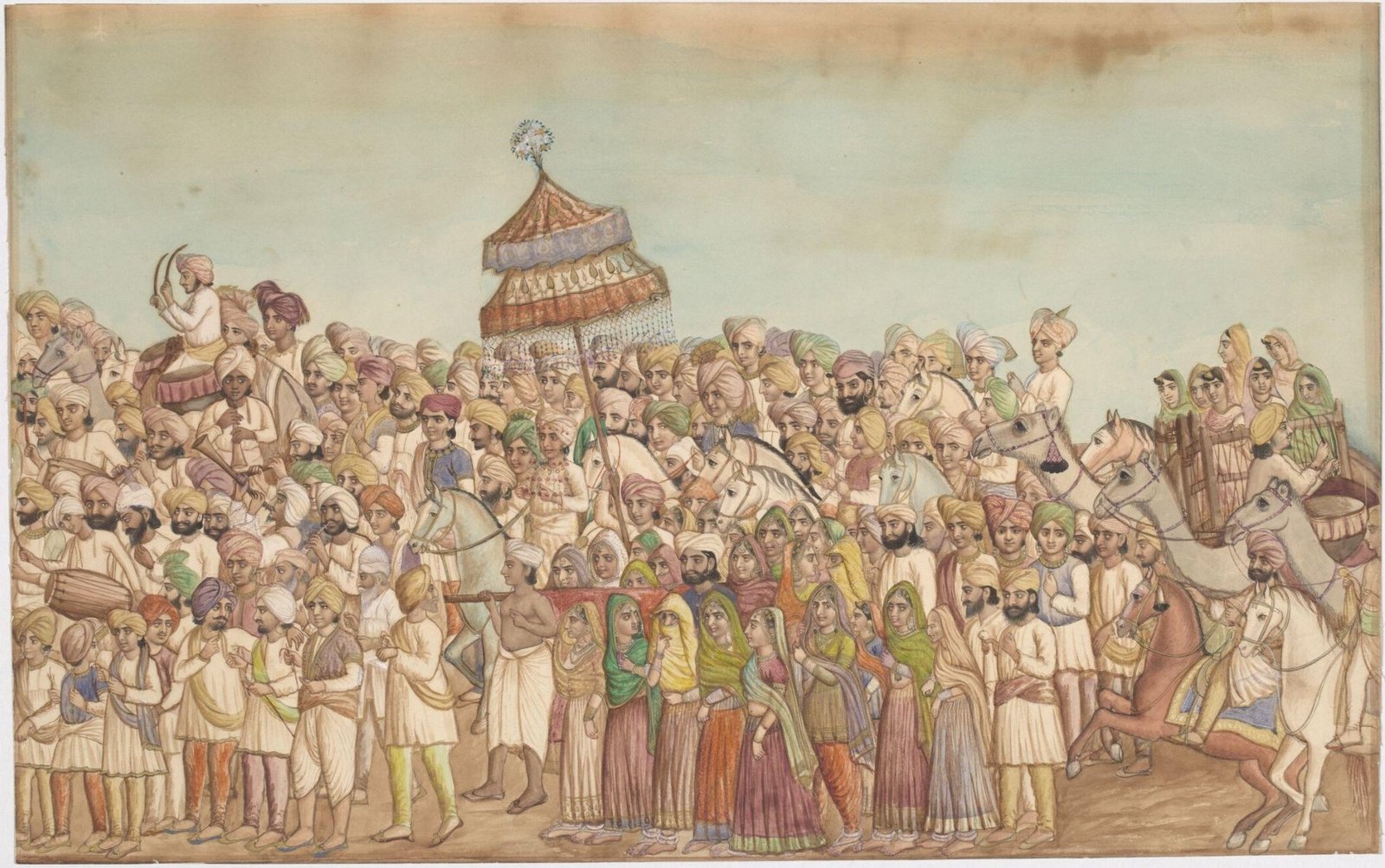

The wedding itself is only the beginning. Marriage in Punjab unfolds over a series of carefully choreographed visits. The bride arrives first as a dulin in a palanquin, accompanied by the barat—the groom’s procession. After one night, she returns to her parental home with her husband in what is called muklawa. Over months, the cycle of back-and-forth continues, each visit marked by exchanges of clothes, sweets, and hospitality.

Finally, after a prolonged stay at her parents’ home, the bride settles permanently in her husband’s household. Her initiation is marked by a simple act: her mother-in-law asks her to cook kechori, a dish of rice and lentils. With this, she assumes her duties as a homemaker, beginning the lifelong rhythm of alternating between her natal and marital families.

These movements embody more than domestic adjustment; they are public rituals of belonging. Every visit cements ties between the two households, weaving networks of obligation and affection that ripple outward through the biradari.

The Bride as Cultural Bridge

In this dance of exchanges, the bride herself becomes the bridge between two families. Her visits home are never solitary; each return carries gifts for her husband, children, and in-laws, while her parents reciprocate with clothes, sweets, and tokens of love.

In this dance of exchanges, the bride herself becomes the bridge between two families. Her visits home are never solitary; each return carries gifts for her husband, children, and in-laws, while her parents reciprocate with clothes, sweets, and tokens of love.

Through her, two households remain tethered. She is not only a wife and daughter-in-law but also a constant reminder of her natal family’s generosity. Her role illustrates how women in Punjabi marriages carry the invisible burden of maintaining kinship diplomacy, ensuring that both families remain bound by ties of respect.

The Cultural Soul of Punjabi Marriage

What emerges from these traditions is a portrait of marriage not as an individual choice but as a cultural institution—one that maintains order, renews bonds, and enacts the values of honor and reciprocity. The elaborate web of ceremonies, exchanges, and expectations transforms marriage into a performance of continuity.

The absence of “love” in these arrangements does not imply lovelessness. Rather, love is expected to grow within the framework of duty, companionship, and family honor. What matters most is not the spark of romance but the durability of relationships between families, anchored in ritual and sustained by gossip, reputation, and izzat.