Islamabad’s Sector F-7, prime real estate, houses barely 2.5% of the city’s workforce

Growing up in Karachi, I remember visiting Islamabad during school summer vacations. It felt like an oasis – planned, green, breathable. Now, returning as a resident, I see a city losing its soul. Islamabad, once heralded as a garden capital, feels increasingly choked by cars. The original 1960s master plan by Doxiadis Associates envisaged leafy parks and orderly sectors, “a city of parks and gardens,” as the brochures promised. It was conceived as a symbol of order and modernity, its sectoral grid and initial focus on manageable scale lauded globally. But somewhere along the way, the plan frayed, then unravelled completely. The relentless pressure of population growth, coupled with a catastrophic failure of governance and imagination, has pushed the city down a familiar, destructive path, a path already calamitously paved by Lahore, the sprawling, smog-choked metropolis to our southeast.

Instead of the people-friendly boulevards Doxiadis envisioned, the Capital Development Authority (CDA) embarked on a relentless campaign of road widening, paving over serenity in the name of speed. Yet, paradoxically, large swathes of the original city remain underutilised. As urban planning consultant Ahmad Khattak noted in 2024, Islamabad suffers from a peculiar imbalance: “a low-density [of] single-family houses in the city center, a lack of affordable housing, and a lack of adequate public transportation choices. These factors encourage the use of personal automobiles.” Sector F-7, for instance, prime real estate, houses barely 2.5% of the city’s workforce, forcing ordinary commuters to undertake long, arduous treks from far-flung communities into the city core. We have, in effect, engineered a city that functions optimally only if you possess a private vehicle, preferably a large one.

Islamabad’s expressway – that triumphant concrete artery meant to unshackle traffic – has become emblematic of this profound failure. Originally planned as a bypass to skirt the city, it morphed, through poor planning and political expediency, into the choked backbone of our daily commute. As one frustrated urban observer quipped, the “Islamabad highway is a classic case study of how poor planning can lead to uncontrolled urban sprawl and poor service delivery.” Instead of protecting the city’s planned boundaries, the ICT/CDA began issuing No Objection Certificates (NOCs) for an explosion of new housing societies on its fringes – Korang Town, Gulberg Greens, Naval Anchorage, and countless others – feeding traffic directly onto the already strained highway.

The official response to this self-inflicted congestion? Not integrated public transport, not demand management, but simply more asphalt. Shifting the pain onto the populace was not seen as a planning failure, but as a justification for further expansion. Lanes were added, bridges raised, signals removed, futile gestures against the inexorable logic of induced demand.

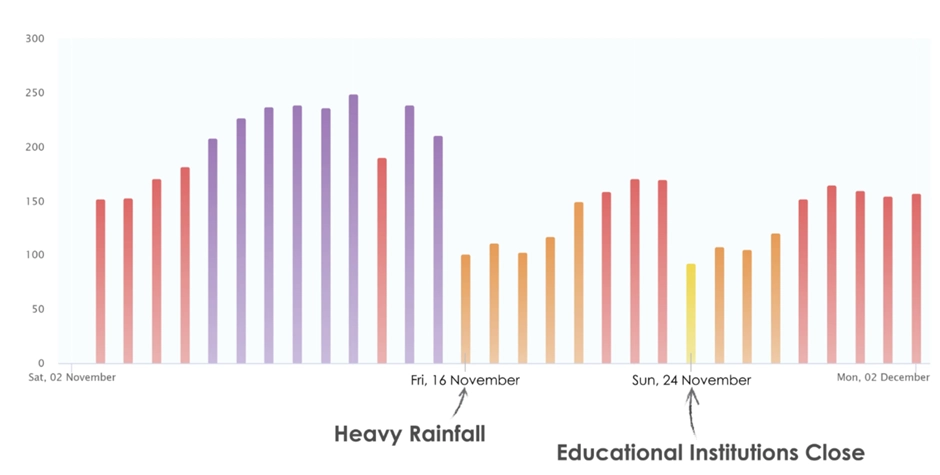

This surge of vehicles does more than just waste commuters’ time; it poisons the air we breathe. Islamabad’s infamous winter smog is a direct consequence of this car-centric model. In the fall of 2024, the capital repeatedly choked as the Air Quality Index (AQI) rocketed above 400, levels hazardous to human health.

An Islamabad traffic engineer’s study confirmed the obvious: vehicular emissions account for over half of the city’s air pollution. In chasing the phantom of smooth traffic flow through endless road building, we are literally suffocating ourselves.

Meanwhile, public transportation in the Twin Cities remains cruel. The Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metrobus, while a positive step, serves only a fraction of the populace, leaving vast areas untouched. Crucially, no integrated metro or express bus routes serve the burgeoning populations along the Islamabad Expressway corridor. The working classes, the majority of the population, have been effectively abandoned, forced to rely on unreliable and dangerous options. While the wealthier citizens can hedge their bets by owning multiple cars per family and retreating into private housing societies.

The War on the Human Scale

This obsession with facilitating vehicular movement isn’t just inefficient; it’s profoundly dehumanising. It wages a daily, undeclared war on anyone not encased in a ton of metal and glass.

Crossing a major road artery requires Olympic-level agility, bravery, and a hefty dose of fatalism. Are our cities designed with anyone on foot in mind? The answer, etched in the broken pavement and the terrified faces of pedestrians dodging traffic, is a resounding, shameful no!

This anti-pedestrian bias has rendered our streets dangerously hostile. Safe, continuous sidewalks are a luxury, not a right, in Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Pedestrians have to get on and off the walkway constantly, weaving precariously into the flow of traffic to find a path forward.

This contempt for the foot traveller is not just an inconvenience; it is an indictment of our urban values. By design or, more likely, by sheer neglect, civic agencies have granted automobiles absolute, unchallenged right-of-way. In personal interactions, I have often heard motorists contemptuously refer to pedestrians as “Jahil Awaam” (ignorant masses), as if those outside a vehicle had deliberately chosen to endanger both themselves and the oh-so-important motorist by merely existing in shared space. As columnist Ibne Ahmad wryly commented about the twin cities, “Pedestrians are expected to stay off the roads and not cross anywhere, giving motorists full priority to use the roads the way they see fit… Even our traffic police are in the habit of using words such as jaywalkers to describe victims of automobile violence.”

The irony is stark: most of us are pedestrians at some point every single day, walking from our cars, accompanying children or the elderly, or simply because we cannot afford vehicular transport — yet the city has built virtually no life-affirming infrastructure for this fundamental human activity. Safe, marked crosswalks at major junctions are non-existent; pedestrian bridges are often few and far between, forcing even able-bodied adults into dangerous sprints across multiple lanes of traffic. Where we could have planted shade trees, widened sidewalks, or installed benches, we instead laid more asphalt or simply left the footways to crumble into dust.

This hostile environment isn’t merely about infrastructure; it’s underpinned by a breakdown of rules and respect. Do traffic laws truly exist in practice, or is the road a Hobbesian jungle where might makes right? Traffic police often appear more concerned with facilitating the unimpeded passage of VIP motorcades or issuing token tickets to helmetless motorcyclists than tackling the systemic dangers of excessive speeding, aggressive tailgating (a particularly obnoxious habit of many SUV drivers), and reckless lane-changing (exhibit A: the legions of ride-hailing drivers seemingly operating under their own laws of physics). When fines are a negligible nuisance for the affluent drivers of expensive vehicles, and enforcement is inconsistent, often arbitrary, or perceived as corrupt, the implicit message is clear: the rules don’t apply equally to everyone. Accountability is a phantom concept on our roads.

Despair, however, is a luxury we cannot afford. While the challenges facing Pakistani cities are immense, they are not insurmountable. Cities around the world, many grappling with similar pressures of rapid growth, limited resources, and historical planning mistakes, have demonstrated that a different path, one prioritising human well-being, equity, and sustainability, is possible. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel; we need the humility to learn, the creativity to adapt, and the political will to implement proven solutions.

The writer can be contacted at yasirkk@gmail.com