Anthropologist, filmmaker, and activist Samar Minallah stepped into a world few dared to confront the hidden practice of Swara, where young girls are given away to settle tribal feuds and men’s crimes. What began as an anthropological inquiry became a lifelong mission to restore dignity, justice, and faith to a system that had lost all three.

Over the past fifteen years, Minallah’s work has transformed not only lives but laws. Her award-winning docu-mentaries gave voice to silenced victims and catalyzed national legislation against Swara and related customs such as Vani and Sang-Chatti. Yet, beyond her public achievements lies a story of personal courage of a mother balancing activism with the constant threat to her family, of an academic who turned fieldwork into reform.

In this deeply reflective conversation with Aliya Agha for Margalla Tribune (MT OutLoud Podcast), Samar Minallah speaks about the human cost of tradition.

MT: Samar, your journey into documenting Swara or Vani, as it’s called in Punjab, was groundbreaking. How did this begin?

Samar: It started quite unexpectedly. I was living in Islamabad at the time, far away from rural customs. During an assignment in Peshawar, I heard of this tradition called Swara, in which girls are given in marriage to settle tribal feuds, often after a murder. Everyone I asked claimed the practice had ended. But my background in anthropology compelled me to see for myself. I took my camera, travelled to villages, and discovered that Swara was still happening, only quietly.

In Swat, I found an eleven-year-old girl being given away. That was the first time I saw the face of this practice: a child paying the price for a crime she did not commit.

MT: For readers unfamiliar with Swara, could you explain what it entails?

Samar: Swara occurs when two tribes or families feud, usually after a murder. Instead of punishing the murderer, the jirga (tribal council) decides that one or more girls, often daughters, nieces, or sisters of the offender, will be handed over to the victim’s family “to restore peace.” The murderer walks free, while the girl bears the punishment.

People try to justify it as symbolic reconciliation, but it’s neither moral nor Islamic. The Qur’an is explicit: every person bears responsibility for their own crime. So, this practice not only violates human rights, it violates Islam itself.

MT: Were these girls treated with respect in their new homes or punished further?

Samar: Tragically, most were punished. The idea was that the girl’s presence would remind the victim’s family of their loss, so she became the target of their anger. I’ve rarely found a case where a Swara girl was treated kindly. Many were beaten or sexually abused. One girl in Bhakkar told me she couldn’t even count how many men had assaulted her, just because her brother had married by choice, and she was made to atone for it.

The practice exists across Pakistan: Swara or Irjai in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Vani in Punjab, Sang-Chatti in Sindh, and similar customs in Balochistan.

MT: What is the typical age of these girls?

Samar: Most are minors some as young as three months old. In one case, a baby given in Swara was killed by the receiving family. The cruelty is unimaginable. These girls grow up as servants, living with animals, never treated as humans. I’ve met victims from Kashmore to Swat; their pain is the same.

MT: You turned your research into action and then into law. How did that happen?

Samar: My first documentary brought real women’s testimonies to the public for the first time. I also interviewed religious scholars who affirmed that Swara was un-Islamic. During the MMA government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, we pushed for legislation. Eventually, Section 310-A of the Pakistan Penal Code was amended, those who give or take a girl in Swara can now be jailed for three to seven years.

Through my public-interest litigation in the Supreme Court, over a hundred girls received relief. But laws alone aren’t enough. Implementation remains a challenge, which is why I continue training police and FIA officials, because Swara is also a form of human trafficking.

MT: What do you mean by human trafficking. Could you elaborate?

Samar: Yes. These girls have no agency or consent. They are exchanged like property. That’s trafficking, pure and simple. Recently, I conducted sessions with the FIA to help officers recognise Swara as a domestic form of child trafficking.

MT: After years of advocacy, what keeps you going?

Samar: Initially, I was angry, how could anyone give their daughter to an enemy’s house? But as I met fathers who cried, refusing to surrender their daughters despite pressure, I realised they are the real heroes. Police officers like the late Safwat Ghayur and Abid Ali also stood firm. Ending Swara isn’t just women’s work, it’s a collective moral awakening.

MT: What lesson should society take from this?

Samar: That culture should never be used to excuse cruelty. Real honour lies in protecting life and dignity, not bartering it. Until every girl is safe, our work remains unfinished.

MT: Samar, your work took you deep into dangerous territories, confronting tribal systems and power structures. Were there serious security issues during your activism?

Samar: Many more than I could have imagined. It wasn’t just me at risk; my family was too. Activism sounds noble until your child is on the line. Once, when my son was around eleven, he picked up the phone. A man on the other end threatened him, saying, “Tell your mother to stop, or she will regret it.” That broke me. You can handle threats to yourself, but not to your children.

Yet, my family never asked me to stop. They had seen the faces of those girls with their own eyes, many times my children would accompany me during interviews when they were younger. They understood why this mattered. Over time, I learned to manage it by immediately contacting law enforcement whenever threats emerged, and by being strategic in how I continued the work. Today, I focus more on shifting mindsets and training the police so that protection becomes institutional, not personal.

MT: How long has it been since you began?

Samar: It’s been about fifteen years and it’s still ongoing. Change takes time. Initially, many people didn’t take this seriously; they said, “It’s a domestic issue, not a crime.” Now, after years of awareness and legislation, Swara is recognized as a criminal act. What keeps me going is faith and purpose. As you said, there was really no choice. Once you see injustice of this magnitude, you cannot unsee it.

MT: On a personal level, facing such horrific realities, minor girls being given away, or stories of repeated abuse, how did you cope emotionally?

Samar: Honestly, it changed me. When you witness such suffering, you return home with immense sadness.

The emotional toll was real. I struggled to “switch off.” After witnessing a tragedy, I couldn’t attend a wedding or dinner and just smile. It took me years to learn balance. Even now, I sometimes carry those stories with me.

MT: Rural communities are often uneducated and resistant to change. How did you manage to communicate your message to them?

Samar: That was one of the hardest parts. Many people in rural areas couldn’t watch my documentaries or read articles. So, I had to find another medium. one that travelled where I couldn’t.

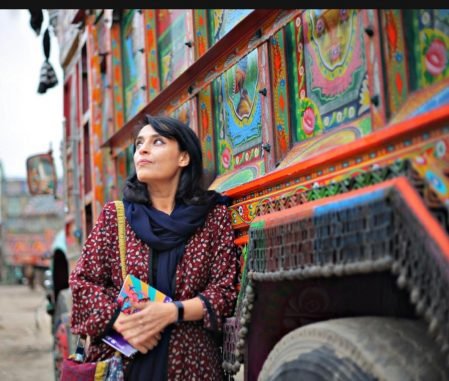

In 2004, while in Peshawar, I visited a truck depot, an unusual place for a woman. I met a truck artist, Hayat Khan. I told him, “You paint lions and film stars on trucks, can you paint a message that says Swara is un-Islamic?”

At first, he refused. He said it would offend people. I asked him to at least paint a father and daughter, with a simple message. Eventually, he agreed. When other truckers saw it, they wanted the same artwork. That’s when I realized art can travel faster than activism.

Soon, trucks carrying the message “Swara is against Islam and humanity” were moving from Karachi to Khyber. Those roads became my awareness campaign. That was the beauty of it, ordinary men like Hayat became my allies. They were the real heroes.

MT: Were there other moments that gave you hope?

Samar: Once in Mardan, there was an 8-year-old girl named Marina who was about to be given away in Swara. I met her and felt as if she were my own child. I pleaded with the jirga elders and explained that what they were doing was un-Islamic and illegal.

Later, I heard that the jirga decided to spare the girl and instead transfer a piece of land as compensation. When I returned, the family was in tears, they couldn’t believe the decision had changed. They prayed for Pakistan’s government, not realizing that it was their own conscience that had shifted. That moment made me believe change was truly possible.

Hope lives in the courage of those who say “no” to injustice, whether it’s a father refusing to give his daughter, or a truck artist choosing to paint truth instead of silence. Every act of defiance, no matter how small, chips away at a centuries-old system.

Change doesn’t come overnight. But when it comes, it begins in the human heart. And that is where I place my faith.

MT: Your work took you deep into dangerous territories, confronting tribal systems and power structures. Were there serious security issues during your activism?

Samar: More than I could have imagined. It wasn’t just me at risk; my family was too. Activism sounds noble until your child is on the line. Once, when my son was around eleven, he picked up the phone. A man on the other end threatened him, saying, “Tell your mother to stop, or she will regret it.” That broke me. You can handle threats to yourself, but not to your children.

Yet, my family never asked me to stop. They had seen the faces of those girls with their own eyes. Many times, my children would accompany me during interviews when they were younger. They understood why this mattered. Over time, I learned to manage it by immediately contacting law enforcement whenever threats emerged, and by being strategic in how I continued the work. Today, I focus more on shifting mindsets and training the police so that protection becomes institutional, not personal.

MT: How long has it been since you began?

Samar: It’s been about fifteen years, and it’s still ongoing. Change takes time. Initially, many people didn’t take this seriously; they said, “It’s a domestic issue, not a crime.” Now, after years of awareness and legislation, Swara is recognized as a criminal act.

What keeps me going is faith and purpose. As you said, there was really no choice. Once you see injustice of this magnitude, you cannot unsee it.

MT: On a personal level, facing such horrific realities, minor girls being given away, or stories of repeated abuse, how did you cope emotionally?

Samar: Honestly, it changed me. When you witness such suffering, you return home with immense sadness.

The emotional toll was real. I struggled to “switch off.” After witnessing a tragedy, I couldn’t attend a wedding or dinner and just smile. It took me years to learn balance. Even now, I sometimes carry those stories with me.