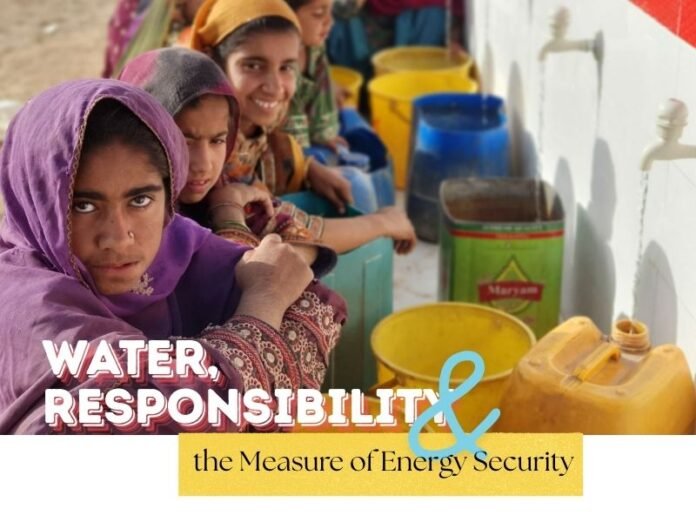

Energy security in Pakistan is often discussed in megawatts, pipelines, and barrels. Yet, for communities living near oil and gas fields, security is measured far differently: in clean taps, functioning wells, and safe water for children. In these quieter, less publicised spaces, Oil and Gas Development Company Limited (OGDC) is quietly redefining what it means to be a responsible state-owned energy company.

The Water Challenge at the Margins

Pakistan’s water crisis is no abstraction. Groundwater de-pletion, contamination, and seasonal shortages make acc-ess to clean drinking water an urgent, everyday strug-gle. In regions like Chakwal, where OGDC’s Rajian Oil Field op-erates, these pressures are amplified. Villages here exper-ience water scarcity that directly affects health, livelihoods, and local resilience. It is in this context that OGDC’s inter-ventions, while modest in scale, carry significant meaning.

Rajian Oil Field: Infrastructure Meets Necessity

Around the Rajian field, OGDC has focused on rehabilitating and installing water infrastructure: tube wells, pressure pumps, filtration units, and water bowsers. These projects are not one-off gestures, they form a structured approach to restoring access where industrial activity intersects with environmental stress.

Importantly, OGDC prioritises rehabilitation alongside installation. Wells that fall into disrepair and filtration plants without maintenance quickly become useless. By restoring broken systems, the company ensures continuity, demonstrating a practical understanding of what “service” means in rural Pakistan.

Emergency Response: Beyond Infrastructure

During acute shortages, clean water is delivered via bowsers to affected villages. These temporary measures, while not transformative, address immediate survival needs and reinforce the company’s presence as a local actor. When combined with longer-term infrastructure projects, they create a layered response that addresses both urgency and sustainability.

Investing in Social Capital

Water access is only one dimension. OGDC’s engagement extends to community facilities, including schools in Mulhal Mughlan and surrounding areas. Educational improvements anchor communities, particularly in districts where public investment is thin. Schools with upgraded infrastructure are more than classrooms, they are lifelines, particularly for women and children, in areas where state services struggle to reach.

The installation of Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants in villages like Gorsian highlights another critical dimension: water quality. In many rural areas, groundwater may be plentiful but unsafe, affected by salinity or contamination. RO systems offer a tangible health benefit, addressing the silent crisis of waterborne diseases that disproportionately affect children.

Transparency and Accountability Gaps

Not every community benefits equally, and villages such as Mogla are not explicitly documented in public CSR reporting. This underscores a wider challenge: corporate transparency. As Pakistan aligns more closely with global ESG standards, OGDC, like other state-owned enterprises, faces pressure to produce granular reporting that reflects real, local-level impact rather than aggregate statistics.

Trust and the Social Licence to Operate

What sets these interventions apart is their potential to foster trust. In extractive regions, perceived neglect can quickly harden into resentment, threatening social cohesion and operational stability. Sustained investment in basic services helps secure what corporate governance scholars call a “social licence to operate,” community acceptance of industrial presence, grounded in tangible benefits rather than promises.

A Wider Policy Lesson

Pakistan cannot resolve its water crisis through govern-ment effort alone. Fiscal constraints, climate pressures, and administrative gaps demand broader participation. Here, state-owned enterprises can play a decisive role. When energy companies invest in water resilience, they do not stray from their mandate, they secure the social and environmental foundations upon which that mandate depends.

Scaling Impact and Clarity

The path forward for OGDC is clear. Best practices should be scaled across all operational areas, ensuring consistent water quality, maintenance, and community engagement. Equally important is communication: detailed reporting that shows real-world impact at the village level, not just company-wide metrics. Only then can CSR initiatives claim legitimacy beyond headlines.

Redefining Energy Security

It is not just the electricity that lights homes or the gas that fuels industry. It is also the clean water that flows from taps in villages near Rajian, Mulhal Mughlan, and Gorsian. In these taps, the abstract notion of corporate responsibility is transformed into tangible relief, daily, quietly and significantly.

OGDCL’s efforts may not solve Pakistan’s water crisis. But they illustrate a critical principle: true energy security extends beyond pipelines and production figures; it encompasses the well-being of communities that live in the shadow of extraction. In recognising this, OGDC offers a model for what state-owned enterprises could and arguably should achieve when they align operational activity with social accountability.