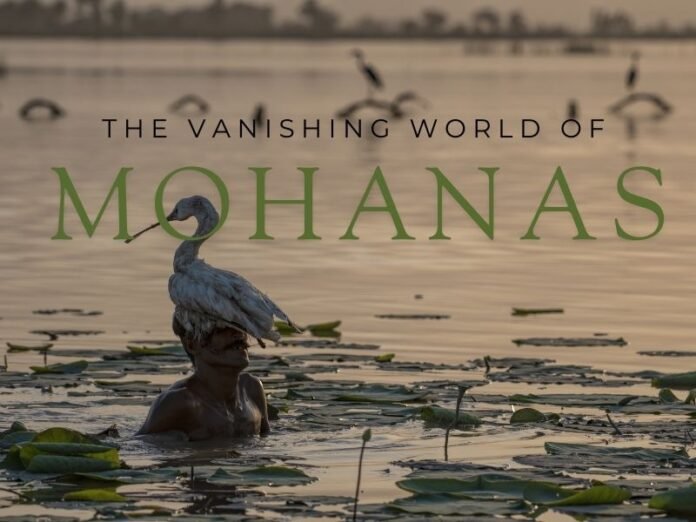

On the wide, troubled waters of Manchar Lake, once the beating freshwater heart of South Asia, lives a commu-nity the world has almost forgotten. The Mohana tribe, an ancient indigenous community often called “bird fishermen” for the way they trained water birds to hunt alongside them, now navigates a slow-moving human-itarian and ecological collapse.

Manchar Lake should be a national ecological treasure. Located in Sindh province, it was once Asia’s largest shallow freshwater reservoir, sustaining fisheries, migra-tory birds, and entire floating civilizations. Today, it stan-ds at a cautionary point of how climate stress, environ-mental mismanagement, and institutional paralysis con-verge into social erosion.

Erratic rainfall in the Kirthar mountain range has redu-ced natural inflows. Declining Indus River flows, diverted by upstream dams and irrigation networks, have weak-ened seasonal recharge. From over 250 square kilo-metres in healthy cycles, the lake has shrunk to nearly a quarter of its historical size. Lower water volumes con-centrate pollutants, raise salinity, and weaken ecological resilience.

For the Mohanas, this is not an abstract environmental statistic. It is the slow disappearance of home.`

“People living beside one of the world’s great freshwater lakes were bringing drinking water from elsewhere. They cannot drink water from the lake anymore. Fish biodiver-sity has collapsed, only very small fish remain. And today, you cannot even see lotus or aquatic plants across the lake surface the way you once could.”

What was once a lifeline has become a toxic trap.

Birds, Lotus, and the Breaking of Ecological Memory

Manchar Lake historically served as a critical wintering site for migratory birds traveling thousands of kilometres from Siberia and Central Asia, hosting over 100 bird species and tens of thousands of seasonal visitors. Long-term habitat degradation has sharply reduced bird numbers, reflecting declining food resources and wetland quality.

Today, lotus beds have nearly vanished, casualties of sali-nity and chemical contamination. Even bees that once po-llinated the wetlands have disappeared. The ecosystem is unravelling layer by layer. For the Mohanas, this is not mer-ely biodiversity loss, it is cultural erosion.

Bonded Water: Poverty Under the Contractor System

Environmental collapse has collided with exploitative eco-nomic structures.

In Punjab, fishing operates under a contractor system, wh-ere fishing rights are auctioned at prohibitively high prices. Local fishermen cannot afford permits and become labourers for contractors.

“Today, 20 fishermen caught only about 40–45 kilograms of fish. The total income was about Rs. 3,500, divided among 20 people. That is barely survival.”

Many families borrow advance loans from contractors for weddings or emergencies, trapping them in cycles of bonded labour.

Najam explains the daily economics:

“Extreme weather, heat, cold, unsafe boats, life is phy-sically punishing and economically hopeless,” Najam says. “Some families are now abandoning fishing altoge-ther and seeking agricultural labor in sugarcane fields.”

A Civilization Older Than the State

The Mohanas are often described in development reports as a marginal fishing community. But that framing misses the deeper truth of who they are.

Margalla Tribune’s conversation with Najam ul Hassan, a long-time researcher and social activist working closely with Mohana families, reveals Pakistan’s cultural diversity slipping away. Najam stresses that their identity predates modern Pakistan and even modern history itself.

“The Mohanas should not be viewed only through the lens of poverty or marginality,” he explains. “Historically, their roots trace back to the Indus Valley Civilization. Archaeological amulets from Moen jo Daro show flat-bottomed boats with huts and birds, remarkably similar to how Mohana boats look even today. These symbols are not coincidence. They reflect continuity of river culture spanning thousands of years.”

Locally known as Mallah or Mirbahar, meaning “Lord of the Sea,” the Mohanas sustained themselves through fish-ing, boat-making, bird-assisted hunting, and ecological knowledge transmitted orally across generations.

To the Mohanas, water was not merely a livelihood. It was territory, archive, teacher, and inheritance. Their floating homes were engineered for mobility and survival in shift-ing waters. They never considered themselves landless, water was their land, the lake their village.

From Natural Paradise to Toxic Basin

Manchar historically supported tens of thousands of fa-milies and acted as a freshwater buffer during dry sea-sons. Seasonal floods replenished fish stocks and attrac-ted migratory birds from Central Asia and Siberia.

The first major rupture came in 1958, when a historic drought caused Manchar to dry out completely for the first time. That collapse triggered mass displacement across Sindh and Punjab.

“Families migrated to Karachi’s coastal villages like Mub-arak Village, others settled near Sukkur Barrage, Ghazi Ghat, Alipur, Dera Ismail Khan, and about 30–40 families moved to Taunsa Barrage, where I work closely with them today,” Najam explains.

What followed was even more destructive. The Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD) system began diverting sa-line agricultural runoff and untreated industrial effluent into the lake. Pollution intensified through the 1980s.

“The ecological crisis at Manchar worsened dramatically after industrial waste lines were connected into the lake,” Najam says. “The water became toxic. Where Manchar once supported huge daily fish catches and employment for around 50,000 people, the situation today is heartbreaking.”

When he visited the lake, the reality stunned him.

Floating communities fall outside conventional service delivery systems. They are citizens in theory invisible in practice.

Traditional livelihoods are collapsing not only due to environmental damage, but also governance design.

Invisible Citizens: Identity Without Recognition

Modern governance systems, however, do not recog-nise floating citizenship. Perhaps the Mohanas’ most de-vastating challenge is legal invisibility.

“Around 80 percent of Mohana families here still do not possess national identity cards,” Najam notes. “Registra-tion authority (NADRA) requires a permanent address, but these families live on boats. No address means no identity cards.”

Without documentation, families cannot access health-care, education, banking, social protection, or disaster relief.

“When they go to hospitals, they are sometimes denied services. Children have missed vaccination drives. Only recently did we succeed in bringing polio teams to their settlements.”

Floating communities fall outside conventional service delivery systems. They are citizens in theory, invisible in practice.

Children Without Schools, Futures Without Anchors

Education access remains nearly non-existent.

“There is no system,” Najm says bluntly. “They live on boat houses, and education access is almost non-existent.”

Without schooling, children inherit vulnerability alongside tradition. Cognitive development suffers from polluted en-vironments, nutritional insecurity, and constant mobility. The intergenerational cycle of poverty deepens.

Climate Injustice at Water’s Edge

Environmental collapse remains the root threat.

“Declining river flows, pollution, loss of fish biodiversity, climate variability, and institutional neglect are eroding their livelihood,” Najam warns. “Without legal identity, they remain invisible citizens. Without ecological protection, their culture may vanish entirely. If we lose the Mohanas, we lose a living heritage of the Indus.”

The Mohanas contribute nothing to carbon emissions or industrial pollution, yet absorb its harshest consequenc-es. Their disappearance would represent a moral failure of climate governance and development ethics.

What Must Change

Solutions exist. What is missing is enforcement.

“Rules and regulations already exist. Punishments exist too. The real issue is implementation,” Najam stresses. “The laws are not the missing piece. Enforcement is.”

He highlights reforming the fishing contract system as critical.

“Other provinces have license systems where fishermen can directly obtain permits. In Punjab, fishing rights are auctioned through costly contracts controlled by power-ful networks. Fishermen should receive direct licenses like in other provinces so livelihoods can improve.”

A Civilization Worth Saving

Manchar today is a contaminated basin receiving industr-ial waste, agricultural runoff, and urban sewage. The Moh-anas are not asking for nostalgia or pity. They are asking for recognition, dignity, and survival.

Their story reminds us that civilizations are not only built on monuments and megacities. Some float quietly on wa-ter, carrying ancient knowledge about balance, and coex-istence with nature.

If Pakistan allows the Mohanas to disappear, it will not me-rely lose a tribe. It will lose a living memory of ancient cul-ture and wisdom.

About Syed Najam Ul Hassan

Syed Najam Ahmed is an industrial safety specialist hea-ding fire safety at the Kote Addu Power Plant near Taunsa Barrage, a lifelong documentary photographer, and the author of a visually powerful book documenting the life and culture of the Mohanas, titled “Mohanas of Indus- a Photographic Odessey”.

Photography by Najam Ul Hassan (Images are subject to Copyright).