Aisha Imdad approaches painting the way one might enter a remembered garden, with the awareness that beauty reveals itself only to those who linger. Her worlds unfold in a miniature sensibility, layered with histories that gently draw the viewer toward imagined gardens of Eden.

Gardens, in my view, represent one of our most profound connections to nature. They are spaces where history, memory, and human longing quietly meet the living world.”

There is in her work a tender intelligence that quietly questions how humans borrow and sometimes burden beauty from nature. She stitches Mughal echoes, forgotten myths, and intimate observation into luminous landscapes that invite contemplation rather than spectacle. Aisha’s gardens do not demand attention; they reward it, offering the viewer a quiet, enduring intimacy with time, memory, and the fragile dignity of the natural world.

Aisha’s professional journey unfolds with a calm inevitability, shaped by both discipline and daring. She was running the programme of MA Hons Arts as a research assistant in Lahore National College of Arts, NCA, and served on the faculty of the NCA in Rawalpindi, later becoming Head of the Department of Art and Design at COMSATS University, where her mentorship shaped a new generation of artists. During the pandemic years, she carried her practice across continents, expanding both her audience and artistic dialogue.

In United States, her work found new resonance through acclaimed and sort after awarded group exhibitions, solo show and art residency. Her work was acquired by Denver Botanic Gardens museum as part of their permanent art collection, affirming her growing international presence and the lasting relevance of her art practice.

Aisha’s engagement with natural forms emerged through her initial academic research, particularly her research of fresco paintings of South Asia. She contributed in international jounals some of her research in form of research articles. This inquiry gradually expanded into broader cultural heritage contributions, including scholarly writing for a UNESCO initiative.

Research, she emphasizes, forms the backbone of her artistic process. Her paintings are never mere representations of flowers, landscapes, or architectural forms; each element carries symbolic weight and narrative depth. Every image is anchored in history, culture, or philosophy, rendering the work layered, intellectually grounded, and conceptually rigorous.

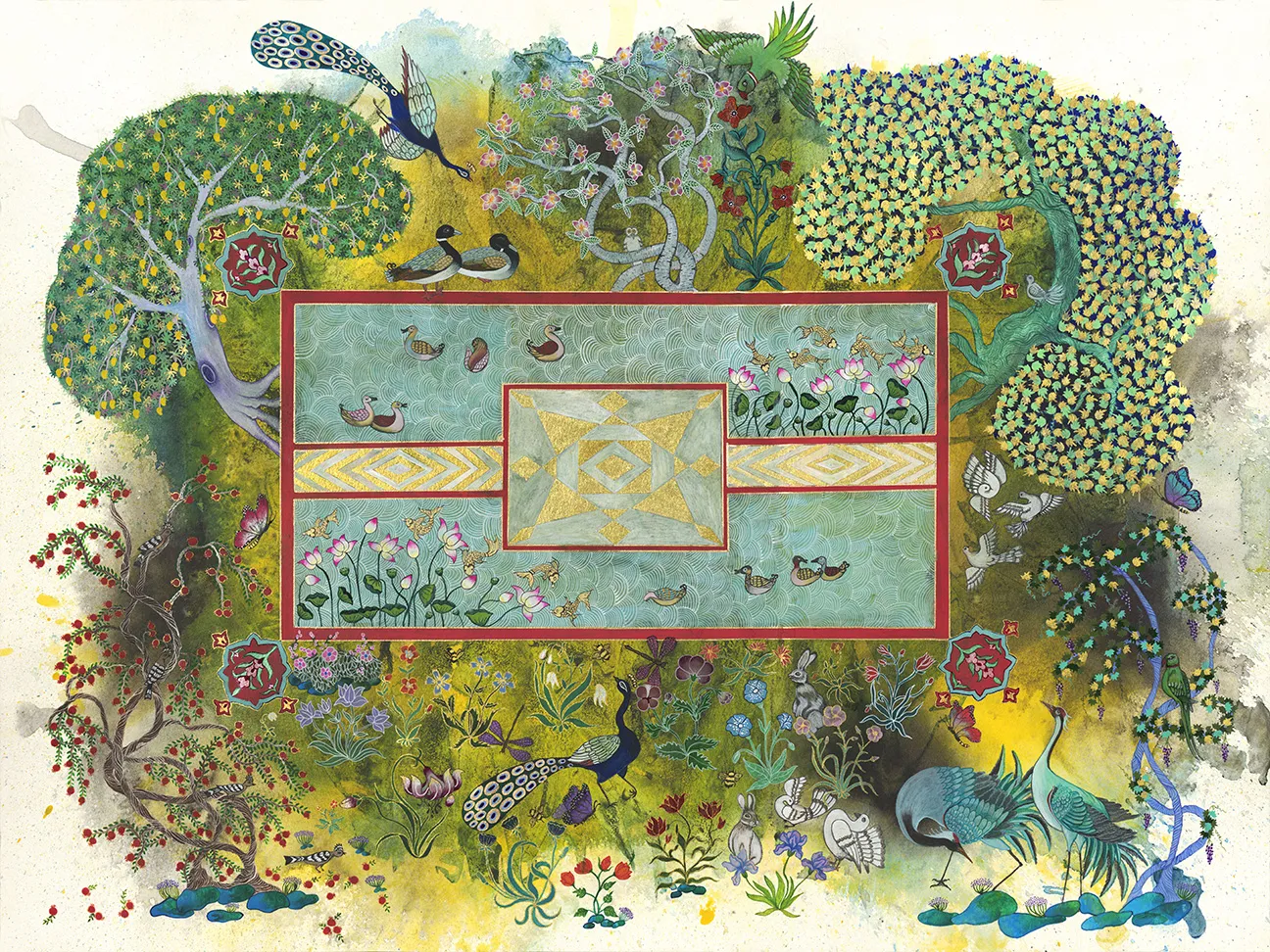

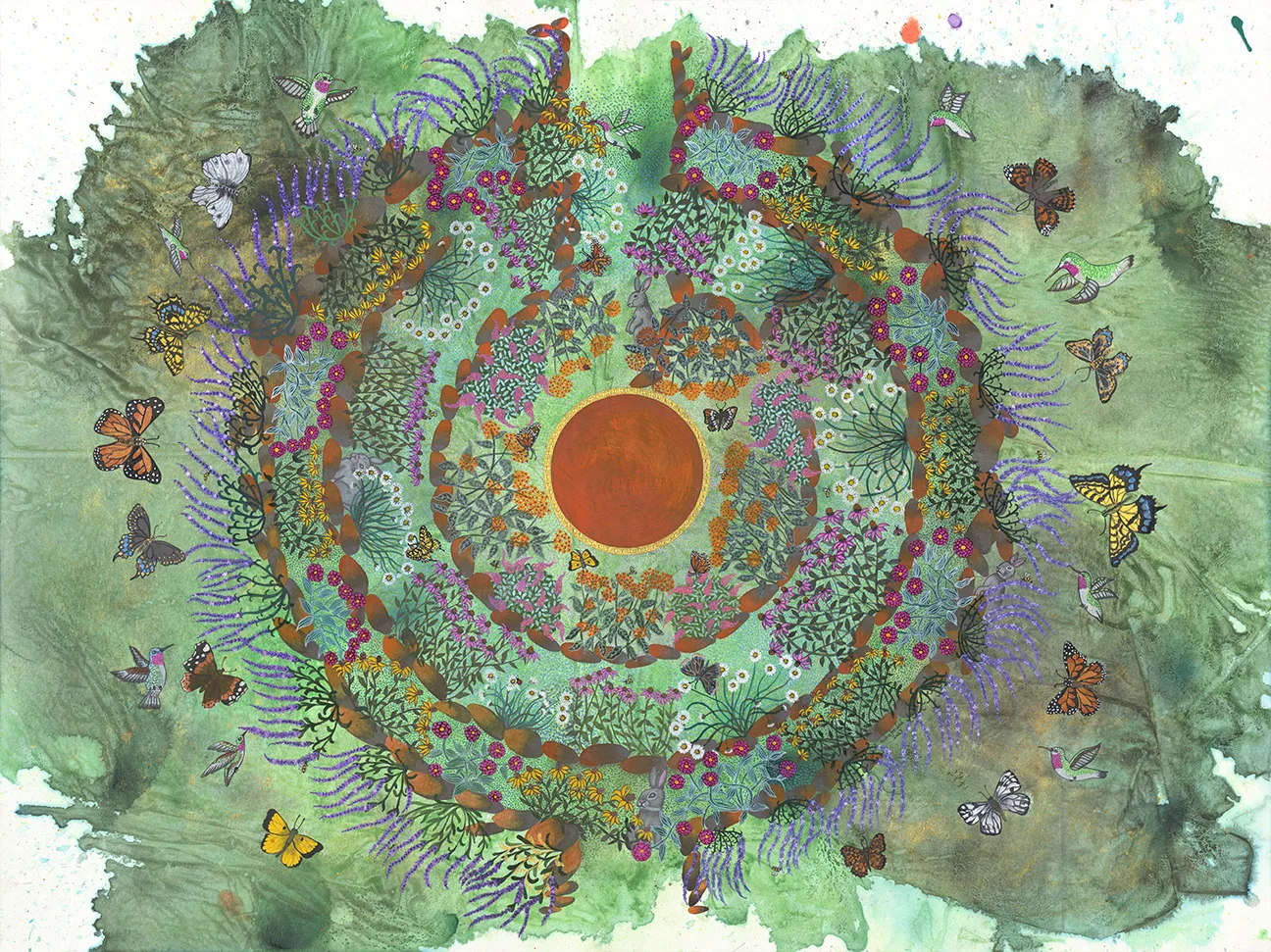

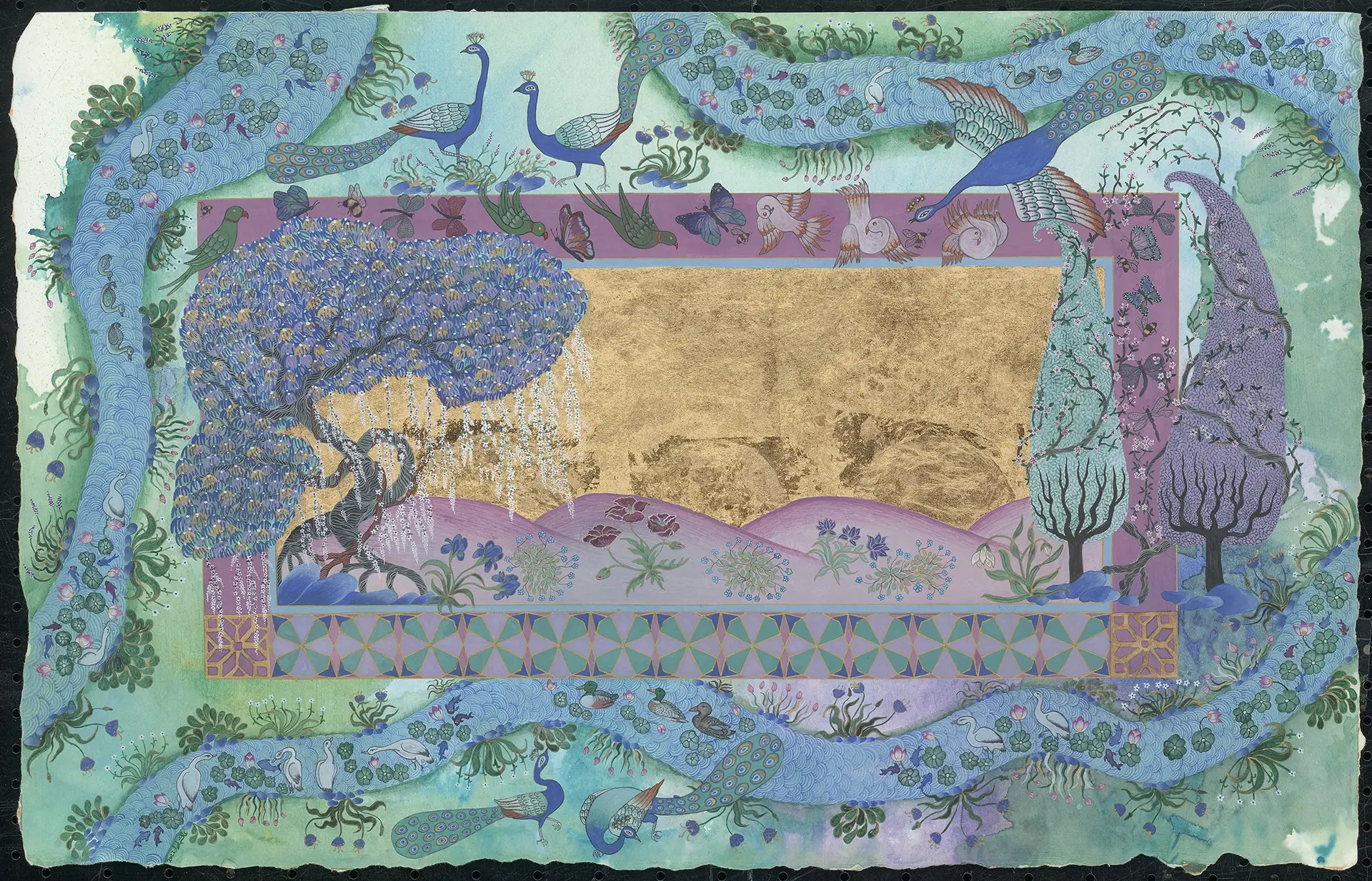

Her visual language draws from Chinese mythology, the lost Mughal garden Bagh-e-Wafa attributed to Emperor Babur, and visual echoes of Monet’s water gardens. Rather than reconstructing these spaces, Aisha reimagines them, creating a dialogue between past and present. Her painting series The Gardens of Eternity: Bagh-i-Wah Series I & II, inspired by Emperor Jahangir’s seventeenth-century gardens in Wah, holds particular personal significance and marked an important moment in the evolution of her practice.

“I study four primary types of gardens: historical gardens, literary, philosophical and poetic gardens, gardens affected by environmental degradation, and contemporary urban gardens.”

This rigor resonates strongly with international audiences. During her exhibitions in the United States, Aisha observed that most artists delve in important issues but few take up serious research based art, a key quality that art curators and critics recognized in her work, often remarking that such depth becomes visible within a single painting. For Aisha, this affirmation reinforces her conviction that research is not a constraint, but a powerful creative instrument.

I am not interested in reconstructing the past. I reimagine these spaces so they can speak to the present allowing memory, myth, and contemporary life to exist within the same frame.”

The Role of Art and the Artist

For Aisha, art is fundamental to preserving humanity itself. Without artists, she believes, society risks losing its emotional and moral sensibility. Artists, in her view, are custodians of hope, restoring sensitivity, bringing colour into everyday life, and offering emotional renewal in a world increasingly shaped by speed, automation, and abstraction. This conviction forms the philosophical backbone of her practice.

“Without artists, society risks losing its emotional and moral compass. Art revives the human spirit, restores sensitivity, and reminds us that beauty still matters in an increasingly mechanical world.”

Spiritual Journeys and Monumental Expression

Spiritual inquiry occupies another essential dimension of Aisha’s practice, particularly through her engagement with The Conference of the Birds, the celebrated philosophical allegory charting the soul’s journey toward truth and divine love. She interprets this inward pilgrimage through large-scale paintings, focusing on the first two stages: the awakening of the seeker and the trials of transformation that follow. She plans in future to paint and complete all the seven valleys or stages mentioned in the book, conference of birds.

Scale remains central to her artistic language, evident not only in these spiritual works but also in an expansive painting inspired by Pakistan’s monsoon season. Together, these bodies of work reflect Aisha’s commitment to exploring spirituality, history, and the enduring capacity of art to connect cultures and reawaken the human spirit.

Aisha’s art ultimately restores wonder with quiet authority, reminding us that beauty is not something to be possessed, but something to be protected, contemplated, and carried forward with care across generations.

Painting I — Bagh-i-Wah Series

According to historical accounts, Emperor Jahangir is said to have exclaimed “Wah!” — meaning “wonder” — upon witnessing the gardens’ beauty, giving the site its name. The central pool reportedly once housed royal fish adorned with pearls in their noses — a detail that lingers today as legend, even as the fish now swim unadorned.

In this series, Aisha weaves together fish, flowing streams, birds, Mughal botanical motifs, and architectural rhythms to create layered visual narratives that merge history with imagination. Folklore, ecological memory, and imperial aesthetics coexist within her compositions, allowing the garden to emerge not merely as a place, but as a living archive of cultural memory, transformation, and enduring beauty.