In Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, drug addiction has evolved into a widespread crisis with far-reaching social and public health consequences. Once confined to the margins, substance use now cuts across both urban centres and rural districts, affecting households, educational institutions, and entire communities. The most commonly used drugs—hashish and heroin—remain pervasive, but the landscape is changing fast with the alarming rise of methamphetamine, known locally as “ice.” Its rapid spread, particularly among the youth, has heightened the urgency for intervention. What was previously considered a peripheral concern has become a national challenge that demands coordinated action from healthcare providers, law enforcement agencies, policymakers, and civil society organizations.

The scope of the crisis is underscored by data from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which estimates that 7.6 million Pakistanis use drugs, with 4.25 million in need of urgent treatment. In regions like Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, heroin use has reached alarming levels, with 77% and 66% of respondents, respectively, reporting its regular presence in their communities. Yet heroin is no longer the gravest threat. Methamphetamine—cheaper, more addictive, and far more destructive—has taken hold, particularly in towns like Kohat and cities like Peshawar. Here, the crisis is not abstract. It wears the faces of sons, daughters, and neighbours whose lives unravel behind closed doors, shielded by stigma and silence.

The drug problem in Pakistan is deeply entangled with geography and geopolitics. KP’s proximity to Afghanistan—a major opium-producing region—has turned it into a corridor for trafficking. Initially smuggled from Afghanistan and Iran, methamphetamine is as easy to get as food delivery.

This normalization has devastating consequences. Unlike hashish—reported by 70% of respondents as common in their area and often seen as “functional,” ice destroys sleep cycles, accelerates paranoia, and leads to psychotic breaks. “Some users stay awake for 96 hours straight.

Some become violent. Some harm their own families”, says a representative of DOST Foundation, an NGO working towards awareness raising, treatment, and rehabilitation of drug users in KP.

In a climate where state response has fallen woefully short, corporate partnerships are filling the gaps. The rehabilitation center supported by OGDCL operates across three locations in KP with over 400 beds and offers a comprehensive 45-day recovery program, including medical detoxification, psychological therapy, and aftercare that extends for up to a year.

These are not luxury rehabs. Most patients here come from impoverished families who could never afford care. Without OGDCL’s CSR funding, their path to recovery would remain closed.

800 Lives and a Promise

Two years ago, OGDCL funded a rehabilitation initiative under its CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) program. Phase 1 successfully rehabilitated over 800 patients, prompting an extension. But numbers tell only part of the story.

At the heart of this effort lies a referral system set up in Kohat, which casts a lifeline to addiction-prone southern districts—Lakki Marwat, Karak, and Hangu. From there, patients are transferred to a residential treatment center in Peshawar. It is there, in those quiet wards and group sessions, that the battle begins.

Holistic Treatment

Only 11.2% of addicts in Pakistan ever receive care. The reasons are manifold: cost, stigma, and a national health system that does not recognize addiction as a medical emergency.

Unlike conventional rehab, the DOST model is holistic. It blends medical detox and psychological counseling with spiritual therapy—Nazirah, Quran recitation, structured prayer. It offers skills training, from stitching for women to plumbing for men, equipping survivors with tools to re-enter life with dignity. Recreational and educational activities help reconnect patients to a routine—and to hope.

And this care doesn’t end when they walk out. For six months post-treatment, patients are monitored to reduce relapse—a critical gap often neglected in public systems. a model for others.

The results are remarkable. The center operates with separate facilities for adult males, women, and juveniles, a necessary adaptation in a country where even 9-year-olds have been admitted for ice addiction. One woman arrived addicted to injectable painkillers—a rare case in a nation where only 1.35% of users are injectors, but her recovery became a model for others.

Muhammad Bilal, 39, Lakki Marwat

My struggle with addiction began with casual cannabis use and spiraled into ice (crystal meth), destroying my health, relationships, and sense of self. When I reached my lowest point, I found a lifeline at DOST Welfare Foundation, supported by OGDCL. Their 45-day free treatment program gave me not just recovery, but a renewed sense of purpose. Today, I live in Lahore and work as a tailor, earning an honest living and supporting my family with pride. I’m deeply grateful to DOST and OGDCL for helping me reclaim my life.

Aamir, 18, from Kohat

I lost my way after falling into bad company and became addicted to ice (crystal meth). I dropped out of school, my health deteriorated, and I pushed my family away. With the support of my brothers, I entered a 45-day treatment program at DOST Welfare Foundation, funded by OGDCL. It was tough, but the care and guidance from their team gave me hope and helped me heal.

Today, by the grace of Allah, I’m drug-free and working with my brothers as a butcher, earning honestly and living in peace. I’m deeply thankful to DOST and OGDCL for helping me find my way back. If I can recover, so can others.

Triggers Behind Addiction and the Trap of Relapse

The reasons why individuals turn to drugs are tragically familiar, often rooted in a mix of vulnerability and circumstance. According to WHO EMRO, most addicts fall between 15 and 35 years of age. Many are unmarried, unemployed, and undereducated. According to data gathered by the DOST Foundation, 37% of users began using drugs for recreational purposes, seeking escape or euphoria in moments of boredom or peer influence. Another 34.5% cited sheer curiosity—an innocent experiment that spiralled into dependency. For 14.3%, the trigger was far more painful: trauma or a life-altering event that left them emotionally fractured and searching for relief. But the journey doesn’t end with detox. Relapse remains a constant threat. The DOST team openly acknowledges that long-term recovery is incredibly difficult, not just because of the chemical grip of addiction, but due to the social and emotional pressures that surround patients after treatment. Many fall back into the abyss—not because they want to, but because the people around them pull them in. Social circles, old habits, and even family members who never believed in their recovery become powerful forces against healing. In this fight, recovery is not a destination—it’s a daily decision to resist, and often, to do so alone.

The Real Cost of Treatment

When it comes to addiction recovery in Pakistan, the cost of treatment remains one of the most formidable barriers, especially for the most vulnerable segments of society. The average cost per patient at the DOST Foundation’s rehabilitation centers, supported by OGDCL, is approximately Rs. 67,000 to 68,000.

This figure covers a comprehensive package that includes not only medical and psychological care but also administrative oversight, awareness-building campaigns, and long-term case management. In stark contrast, private rehabilitation facilities in the country can demand up to Rs. 4 lakh per month, while government hospitals may charge as much as Rs. 3 lakh per patient—amounts that are entirely out of reach for low-income families.

In this context, the OGDCL-backed program is not just generous—it is lifesaving. By making the treatment entirely free of charge, the initiative opens doors that would otherwise remain firmly shut for thousands of people in desperate need. With a total project allocation of PKR 54 million, OGDCL’s contribution illustrates the untapped potential of corporate social responsibility to address urgent social crises. At a time when drug rehabilitation is often overlooked in mainstream CSR portfolios, this intervention stands as a model for how the corporate sector can step up, not only as a benefactor but as a meaningful partner in public health and human dignity.

Kamran, 33, District Kohat

My journey into addiction began with cigarettes and spiraled into cannabis, ice, and eventually heroin. I lost my education, my family’s trust, and almost my life. But my brother never gave up. He brought me to DOST Welfare Foundation, where—thanks to OGDCL—I received 45 days of free treatment. The care and dignity I was shown gave me a second chance. Today, I’m drug-free and working in Qatar as a professional driver, supporting my family with pride. DOST and OGDCL helped me rebuild my life, and they can help others too.

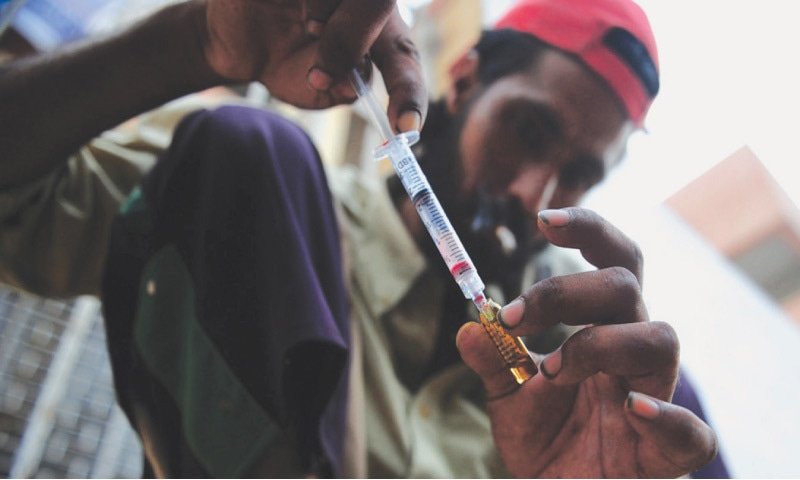

Addiction Brings a Public Health Emergency

Beyond the psychological and social toll, Pakistan’s drug crisis also carries a dangerous and often overlooked public health dimension. While the majority of drug users consume substances through smoking or sniffing, a small but significant portion injects drugs—a practice that brings with it a high risk of transmitting infectious diseases such as Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and syphilis. These bloodborne illnesses not only jeopardize the health of the user but also pose a wider community threat through unsafe practices and lack of awareness. At the DOST rehabilitation centers, supported by OGDCL, every patient is systematically screened for these conditions as part of the intake process. Those found infected are referred to local hospitals where they can receive treatment free of charge, ensuring that another critical health gap is addressed. This proactive approach underscores the interconnected nature of addiction and public health, and the urgent need to treat substance abuse not in isolation, but as part of a broader healthcare response.

According to UNODC 7.6 million Pakistanis use drugs; 4.25 million in need of urgent treatment. The most commonly used drugs—hashish 66% and 77% heroin; an alarming rise of methamphetamine, known locally as “ice.” ice destroys sleep cycles, accelerates paranoia, and leads to psychotic breaks. Only 11.2% of addicts in Pakistan ever receive care. WHO EMRO states addicts fall between 15 and 35 years of age.

The Policy Vacuum

Until as recently as 2022, Pakistan had no legal provision explicitly banning methamphetamine, commonly known as “ice.” This absence of legal recognition allowed the drug to spread rapidly, particularly among the youth, with devastating consequences. Even today, enforcement remains inconsistent. Treatment infrastructure is grossly inadequate, with government-run facilities stretched far beyond their capacity. In Kohat, for instance—a region grappling with widespread addiction—there are only 25 rehabilitation beds available to serve a population where tens of thousands are believed to be in need.

What makes the crisis even more insidious is the deafening silence around female drug users. The UNODC report revealed a troubling gender disparity in data collection: while 276 responses focused on male drug use, only 122 addressed women. As one representative from the DOST Foundation noted, “We don’t even know how deep the problem runs among women. They are invisible.” That word—invisible—echoes through every layer of this crisis. Because this is not just a story about drugs. It is a story about a nation turning its gaze away—from broken systems, from unsupported youth, and from families grieving silently behind closed doors.

The Time to Act Is Now

This is no longer just a health issue—it is a national reckoning. A reckoning with our systems, our stigmas, and our neglect. Until we name the enemy, until we build treatment systems that are just, inclusive, and accessible, and until we replace whispers with clear, collective voices, this epidemic will continue its quiet devastation—stealing our children, dismantling our communities, and eroding our future.

The clock is ticking. And in the face of such urgency, silence is not neutrality. Silence is complicity.